This article explores the evolution and key functions of product managers (PMs) across different eras, from consumer-focused industries to software and internet product management. It covers the responsibilities of PMs in identifying user needs, creating value-driven products, and optimizing business processes to drive growth. The article also delves into the relationship between enterprises, products, and users, offering insights into how PMs design and refine product models to enhance user satisfaction and market fit. Additionally, it discusses the importance of transactions as a means of value exchange and highlights strategies for PMs to reduce transaction costs, optimize efficiency, and balance long-term value with short-term user satisfaction.

Chapter 1: What is a Product Manager?

1. The Three Phases of a Product Manager:

Product Managers in the Consumer Era, Starting from Procter & Gamble: With the rise of mass industrial production, products began to focus on market sales. As a result, activities around product marketing gradually increased. A "single person responsible for a brand" became necessary, with the product manager overseeing aspects such as product positioning, sales, channels, and managing the product lifecycle.

Product Managers in the Software Era, Focused on 2B Software Production: In this phase, the product manager was primarily responsible for software production related to business-to-business (2B) applications. Their duties included research and development (R&D), project management, and sales. The responsibilities of a product manager were divided into three categories:

During this phase, the software market was a seller’s market, where products were not lacking buyers. Instead, the bottleneck was in the development process, with the shortage of excellent engineers. Focusing on product production coordination created more value.

Product Market Manager: Researching user needs, conducting interviews, and small-scale data surveys.

Product Manager: Developing product functional solutions.

Project Manager: Managing the team and coordinating delivery.

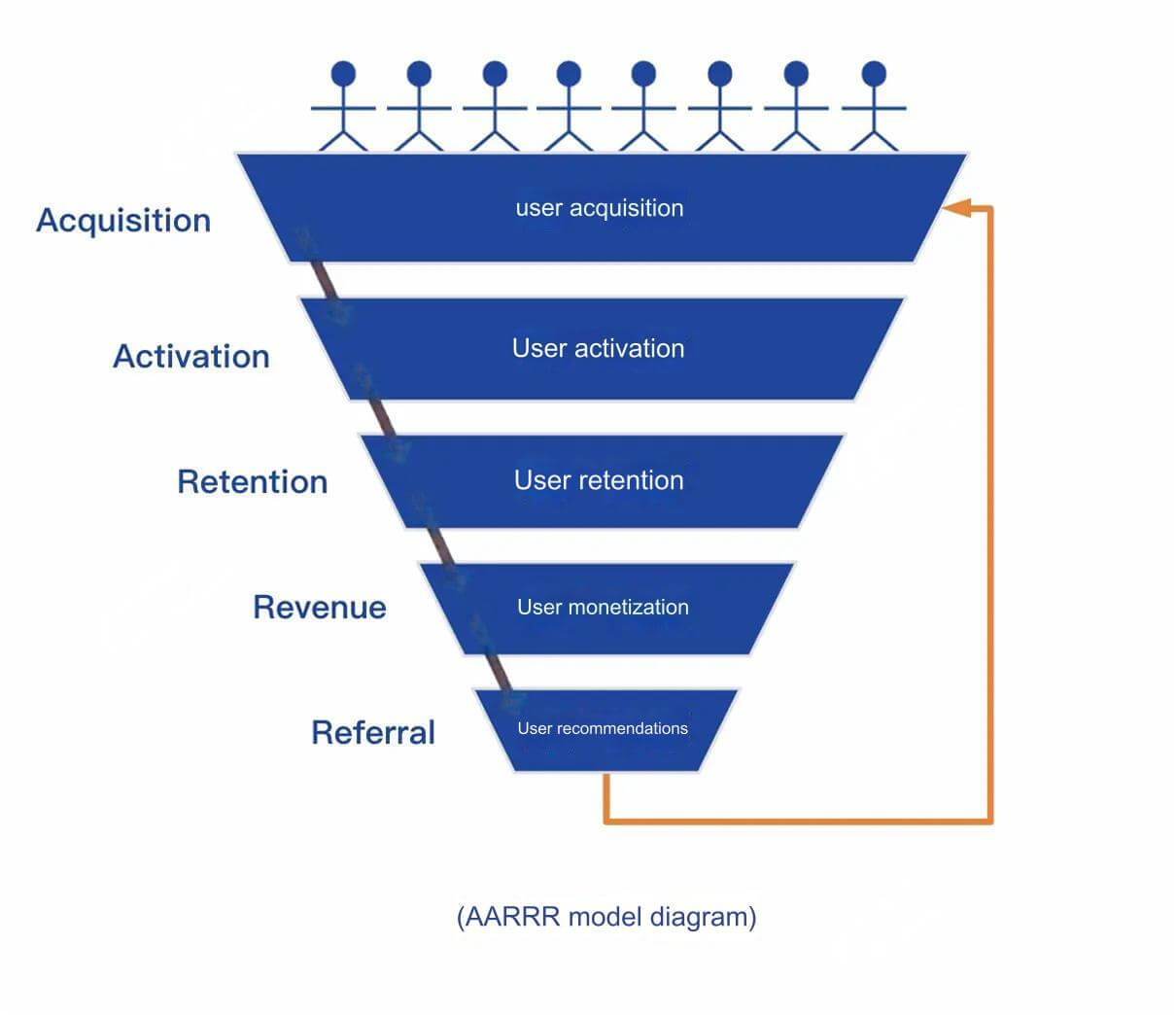

Internet Product Managers: A Combination of Functions Around Business Needs: The role of the Internet product manager emerged in response to the following trends:

In these three phases, with the increase in production capacity and the shift from physical to virtual products (or more precisely, the nature of the product itself — "solutions" — has not changed, but its value is no longer carried by tangible objects, but by intangible information), products can reach more users in real-time. As users become the direct object of the product’s effect, the product’s core value gradually shifts towards the user side.

A good interpretation of the role of Internet product managers is: they are the "connectors" of society, who integrate and output value as the core, managing the value creation process. In this sense, product managers are seen as designers of new social infrastructure (managers of resource usage).

Decline in Marginal Cost of Information Replication and Distribution: With the reduction of marginal costs in information replication and distribution, products could reach a much broader user base. Good products could quickly acquire a large number of users, as the scope of the demand side expanded and the diffusion of products accelerated. The limitations of product use scenarios were significantly reduced.

Rapid Product Iteration and Enhanced Data Utilization Efficiency: Products could undergo real-time A/B testing to gather feedback, aiding product managers in making decisions and enabling fast iteration. Market Fit (PMF) validation became key. The cycle from decision-making to implementation and feedback sped up, allowing quicker market validation and product adjustments. With the aid of data, product managers could "feel" the users' needs and adjust strategies rapidly. However, this rapid response could lead to an overemphasis on "short-term user satisfaction," which might obscure long-term value. Therefore, maintaining sensitivity to long-term value becomes a key judgment criterion for experienced product managers.

Increased Importance of Design and User Experience: Good experiences lead to more effective value circulation and lower transaction costs, strengthening product dissemination. As the internet became the primary channel for product distribution and usage, it also became a medium for information exchange, allowing every user to voice their opinion. This democratization of feedback created an environment where user experience became crucial.

2. The Four Major Functions of an Internet Product Manager:

Demand: Identifying and researching user needs, prioritizing development, and making product value judgments.

Production: Creating documents, prototypes, and interactions; optimizing strategies and evolving features; mastering complex business models and understanding how solutions evolve within organizational structures.

Sales: Promotion, marketing, growth, and after-sales support.

Coordination: Organizing new business collaborations and planning for growth and scaling.

In summary, a product manager is responsible for understanding the current situation (users, teams, organizations, customers, future markets), leveraging resources to create value, and being accountable for the results. The quality of decision-making is crucial in this process. A product manager needs to understand better than anyone else how to allocate resources and which areas to focus on for maximum value creation. While the "80/20 rule" makes sense, implementing it effectively is extremely difficult. How to do things efficiently and with focus can only be learned through practice.

3. The Core of a Product Manager's Profession:

Building User Models: The user model essentially involves treating users and potential users as the target audience, understanding the needs and response patterns behind their behaviors, predicting the impacts of executing the model, finding the optimal solution under constraints (how macro and micro scenarios affect people's awareness), and adjusting the model accordingly.

Building a Transaction Model: Understanding value exchange and establishing a sustainable, mutually beneficial model. This model includes understanding the value judgments and behavior patterns of various stakeholders. In this transaction model, the product serves as a medium for value exchange between the enterprise and users. Adjusting the product is essentially about adjusting the "utility mix" offered to users. Good products have effective utility, yield, and sustainability.

Regarding the two critical models:

Preset → Validation → Correction and Iteration are key processes for these models.

Understanding the Enterprise: As the value-producing entity, the enterprise needs to focus not only on creating long-term value for users but also on understanding the fairness, rationality, and competitiveness of the value and profit balance across the industry chain. This, in turn, supports the value ecosystem and ensures sustainability.

Understanding the Relationship Between the Enterprise, Users, and Products.

Chapter 2: Enterprise, Users, and Products

1. The Relationship Between Enterprises, Products, and Users:

"Commercial attributes" and "user attributes" are two sides of the same coin, both essential elements that need to be balanced to achieve the goal of "value attributes."

An enterprise exchanges value with users through products as a medium, with the ultimate goal of creating commercial value.

What is being exchanged is not the "medium" (the product) itself, but the various user values behind the product (which can also be understood as the product offering a valuable solution). The product/solution is the core vehicle for value, and the key question is how we package a series of actions that satisfy user needs into this vehicle. Value itself is not limited to money; it can also include time, physical and psychological costs, personal data, support, trust, and commitment. A user’s action is a transaction in itself.

What the enterprise can do is, under given conditions, choose which users' needs to fulfill and which user values to create, in order to facilitate exchange, maximizing marginal returns and ROI. Enterprises need to select the right user group and create the appropriate value for them.

2. Understanding Users:

The users that a product faces are not individual people, but a collection of needs. (In essence, a product uses a general solution to address the problems of a specific group, abstracting, simplifying, and compressing this solution into a "tool.") The core task of a product manager is to study users and ensure the enterprise develops products that meet user needs.

The research is aimed at gradually aligning the predefined user model with real users, understanding the plasticity and variability in user behavior (heterogeneity, situationality, plasticity, self-interest, bounded rationality), and predicting changes in user behavior.

Step 1: Understand the preferences and response models of users and potential users.

Step 2: Study individual cases to understand users (samples), gradually forming a user distribution model.

Step 3: Validate hypotheses and refine the user model.

How to Understand User Behavior:

The four key aspects of understanding user behavior models are: cognition, context, expected utility, and feedback.

User needs originate from cognition. Users are essentially "a function of preferences and cognition," and cognition occurs within a "context" that influences it.

Context triggers users’ perceptions, interpretations, value judgments, etc., shaping their expected utility.

Expected utility affects users' behavior and choices, promoting the use of the product.

Actual usage forms experience, which users will use to correct/strengthen/shift their preferences and cognition.

Analyzing the Mechanisms Behind User Behavior: This analysis interprets the loop from cognition to product usage to feedback from the perspective of the user. It is a user experience model that the product needs to manage and continuously refine. As the user base grows, the needs of different users will diversify into more detailed user distribution models.

How to Understand User Value:

Utility is the degree to which desires are satisfied, while happiness is the long-term positive value we aim to bring to users. User value is reflected in the positive feedback from the user group towards the product. Psychological happiness = utility / desire. User happiness can be increased through two methods: increasing utility and reducing desire.

Increasing Utility: The primary characteristic of utility is its subjectivity. Value is also a subjective judgment that changes with cognition (knowledge of past usage paths) and context (current situations). The essence of product updates is the renewal of problem-solving paths. Therefore, increasing utility can come from enhancing the overall value of new experiences and reducing the costs of old experiences and switching costs. Users will choose a new path when utility - cost > 0.

User Value Formula

Reducing Desire: Desire is both infinite and constrained. The infinite aspect stems from the psychological feeling of deficiency due to comparisons, while the constrained aspect comes from the limitations of reality. Simply put, the "Buddhist approach" to increasing happiness involves controlling desires.

3. Understanding Products:

A product is a medium for the value exchange between users and enterprises. Selling a product is essentially selling a combination of utilities under certain constraints.

The key to understanding a product is: knowing where the product’s benefits (needs) come from, where the benefits (transactions) go, what value it creates (new path - old path costs > 0), and how the value is distributed.

Understanding Product Attributes:

A product has three essential attributes:

Effective Utility - It satisfies user needs.

Profitability - It has transactional value.

Sustainability - It creates long-term value potential (positive feedback).

4. Understanding the Enterprise:

The essence of an enterprise lies in two points: 1) discovering market profit opportunities, and 2) achieving production efficiency superior to the market.

My understanding of this statement is that it applies not just to enterprises, but to organizations as well. The value of an organization’s existence lies in its ability to enhance the analytical and productive capacity of its members, discover opportunities, and operate efficiently. An organization enhances the efficiency of resource conversion and improves the average value output of each person, which is the meaning of an organization’s existence.

Discovering Market Profit Opportunities:

This means identifying new paths for value creation in a sea of chaotic information. This is where product managers can create value for an enterprise. There are three main approaches:

Insight: Creating information asymmetry (gaining an information advantage).

Trial and Error: Overcoming incomplete information (by defining boundaries through bi-directional efforts).

Chance: Dealing with information uncertainty.

Information is constantly changing, and the role of the product manager is to continually create maximum value for the enterprise, find major market profit opportunities, and track shifts in profitable paths. Key changes to monitor include:

Market Path: Changes in the market environment and regulations.

Technology Path: The emergence of key new technologies.

Organizational Path: Long-term changes in organizational capabilities.

Achieving Higher Output Efficiency Than the Market:

An enterprise needs to achieve production efficiency superior to the market, which also involves superior resource allocation and decision-making compared to the market. The professional knowledge that contributes to this is the source of the enterprise’s core competitiveness. Organizational efficiency comes from accumulating common knowledge within the organization and sharing individual tacit knowledge, thus forming a more efficient "processing collective."

The efficiency of organizational operations comes from:

Common Goals/Shared Vision: Maintaining long-term efficiency in one direction.

Operational Mechanisms: Designing systems that include both incentives and constraints, allowing individuals to receive feedback and quickly adjust.

Organization: A collective entity formed by people with common goals working together.

3. Long-Term Organizational Survival:

The significance of an organization’s survival lies in its ability to consistently provide value greater than the external environment’s constraints. To play the survival game well, the organization must focus on:

Environmental Selection: (Making choices based on an understanding of PEST).

Choice Costs and Substitution Costs: (Why an organization chooses a particular path).

Efficiency Management: Including organizational development, incentives and constraints, technological capabilities, cost management, monetization capabilities, and allocation of scarce resources.

4. Organizational Output:

The output of an organization can be understood as value-adding assets, manifested in four areas:

Financials.

Cognition (Knowledge) and Teams: Domain-specific cognitive barriers + team = barriers to business handling capabilities.

Intangible Assets: Including trust and the associated reduction in social costs.

5. The Value of Enterprises in the Internet Age:

The role of internet enterprises has evolved with their rapidly expanding influence and the quick feedback they receive. The frequency of interactions between organizations and individuals has increased, and the rise of social interactions has led to an increase in corporate social responsibility. In fact, internet companies are increasingly participating in public affairs and fulfilling public functions.

In the 1970s (Jensen's production function), enterprise value was mainly considered from the perspective of internal factors. At that time, the boundaries of enterprises were relatively clear, and external rules remained stable, with the enterprise’s capabilities mainly limited by technological capacity.

Today, as enterprise boundaries have become blurred, and the way enterprises transfer value to society has started to change, more external factors need to be considered: marginal costs, network effects, multisided market platforms, knowledge diffusion, the internet's impact on cost reduction, substitution effects, etc. These factors have made enterprises increasingly biological in nature.

The creation of enterprise value is achieved through efficiency: labor, division of labor, expertise [individual efficiency], process + reducing switching costs (specialization) [process efficiency], accumulation [specialized knowledge], economies of scale, transaction costs, and new technologies. Through comprehensive efficiency management, enterprises can achieve better resource conversion capabilities.

Chapter 3: Transactions

1. What is a Transaction?

Transaction = Value Exchange = Product: A product is the medium through which an enterprise and users engage in value exchange (the medium of transaction). "Product is the transaction" in a broad sense considers any conscious human action as a cost.

Why Do We Need Transactions? Transactions occur due to the unequal distribution of value (potential difference). The relative value of each unit of value is different for different parties. What is exchanged is relative value, so it is necessary to find the adaptation of relative value. The goal is to ensure that the value both parties receive is greater than the exchange cost.

The Four Elements of a Transaction: Utility, Marginal, Cost, Supply and Demand Law

Utility: Utility refers to the degree of satisfaction of desires, i.e., how well we can provide what users need.

Desire originates from psychological sensations (from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—curiosity, aesthetics, reputation, power, friendship, love, leisure, etc.), beliefs, emotions, cognition (people need to resolve dissonance), self-esteem orientation (the need to maintain self-consistency), and social cognition (the desire to understand the world). Human desires are diverse and infinite. Happiness = utility / desire, which can be replaced with experience = satisfaction degree / desire. Therefore, in a transaction with users, the product, as a utility combination under constraints, should reasonably control users' desires and effectively enhance their experience.

Marginal: The boundary of the service we can provide while maintaining returns. Attention should be paid to marginal utility, diminishing marginal utility, marginal cost, and marginal profit.

Cost: Includes production costs, opportunity costs, and transaction costs. Apart from the market transaction costs, the product manager (PM) should focus on costs related to customer acquisition and controlling potential transaction costs, especially understanding whether a user is blocked by some cost (potential), such as: bounded rationality, opportunism, heterogeneity preventing the flow of information resources, and the scarcity of certain transactions due to specialization—all of which contribute to rising transaction costs. Lowering costs can be achieved through standardization, network expansion, reducing transaction costs, and improving information (making transaction information stacked, determined, and complete).

Supply and Demand Law: It is important to understand the basic rules of market and price changes. Different users perceive the utility of the same product differently, which leads to different supply and demand curves. Creating maximum user value does not necessarily equate to obtaining corresponding returns (ROI) or being able to provide a "profitable" proposition. It serves as the basis for setting product priorities, and value should be provided according to the supply and demand curve of a specific user group.

2. The Value in Transactions is Subjective

The value that occurs in transactions is subjective: users purchase "expected" benefits with "expected" costs. To understand how to conduct value exchange with users, we need to understand their "subjective value" (new value - old value - replacement cost > 0).

Factors influencing the subjective value of users include:

Self-Perception

Judgment: This includes critical thinking about given goals, reference points (previous vs. new experiences, peer users, stakeholders, etc.), cost judgments (who bears the cost—direct, opportunity, risk, transaction), non-monetary values (life, reputation, collaboration, management, prospects, welfare, values, etc.), and temporal judgments.

Risk: Uncertainty in decision-making and probabilities.

Externalities: Spillover effects in multi-user interactions, where the actions and decisions of one individual or group impact the benefits or harms to others.

From the enterprise perspective, it is essential to adhere to the principle of value exchange with users: "Revenue - Costs > 0." Here, revenue refers to the total value that users contribute to the enterprise, and higher utility results in higher revenue. Costs include the total expenses incurred by the enterprise’s actions (production costs, transaction costs, etc.), including both direct costs and transaction costs.

What is gained and what is given should align with the principle of value exchange.

3. The Core Goal of an Enterprise: Creating Transactions

The core goal of an enterprise is to create transactions (by organizing value creation and pushing it to a high level, creating price differences within user groups, and facilitating transactions).

Establishing a Transaction Model

A transaction model is, in some sense, a business model that balances "value creation" and "value distribution" with multi-party relationships in mind. It must consider the gains and losses of multiple stakeholders and understand the scenarios under which transactions can be facilitated. In addition to the normal value exchange, the model can also account for loss aversion, increasing welfare, incentive compatibility, and so on.

How Should PMs Focus on Transactions?

Insight: Information asymmetry—find exchangeable user value.

Trial and Error: In situations with incomplete information or uncertainty, identify more efficient ways to create value, reduce production costs, and lower transaction costs.

Behavioral Weighting: Sort user behavior investments by the return on investment (ROI) that influences user exchange behaviors and consider long-term ROI to maintain the enterprise’s sustainable development capabilities. Long-term value decisions are the most demanding on the judgment of PMs or enterprise decision-makers.

Chapter 4: Decision-Making

Decision-making is about choice—deciding what to do and what not to do. The goal of decision-making is to maximize value under constrained conditions.

1. Sources of Irrationality in Decision-Making:

Limited ability to acquire information, limited ability to process information (due to human brain limitations), and individual differences. In such situations, it is important to consider leveraging organizational decision-making capabilities beyond one's own limitations.

2. How Should Product Managers Make Decisions?

Always consider maximizing long-term value.

The path for decision-making is based on understanding users' value judgments, and can be approached through:

Minimizing Old Experiences: One way to minimize the impact of old experiences is by choosing user groups that are more likely to be attracted by the new product—those who are easier to sway.

Minimizing Replacement Costs: Make it easy and quick for users to understand, acquire, and use the product.

The book provides many insightful case studies about DiDi (China's ride-hailing service), which are highly instructive. I recommend referring to the original book for more details.

3. Decision-Making Methods

Data-Driven Decision-Making: A/B testing, gray releases, user data analysis.

Logical Decision-Making: Reasoning.

Subjective Judgment: Subjective judgment mainly involves constructing simplified mental models, with optimization achieved through a cycle of hypothesizing (storytelling, as the human brain processes this well), validating, and revising.

4. Execution:

Product managers need the ability to deliver outputs and push for implementation by driving the agenda forward. This part, although easy to talk about, is actually a significant test of personal capability during implementation.

Chapter 5: Selecting and Developing Product Managers

Good products are a necessary condition for developing good PMs. The value of a product position is determined by Value (Work) × Success Rate (Team) × Reward after Success. The value of a PM is determined by Experience Level × Platform Fit × Wisdom Level. For more details on the specific factors, please refer to the original book. This chapter highlights the sections that discuss key capabilities of outstanding product managers.

1. Standards for Measuring Product Manager Ability:

1. Two Models

User Model: Accumulation + Analysis + Accuracy

Mastering the user model involves accumulating a large number of user cases and experiences through hands-on experience, user feedback, bad case analysis, data analysis, and extensive hypothesis testing and iterative validation, until user behavior predictions post-launch have a high degree of accuracy.

Transaction Model: Study the product from a transactional perspective + Build a mutually beneficial and sustainable transaction model.

The key to mastering the transaction model is a thorough understanding of transaction costs in a specific domain, as well as an understanding of the multi-party benefits and evolutionary processes in game theory.

2. Operational Capabilities

Scientific Methods: Logic, probability, controlled experiments, rational decision-making, and relevant economic methods.

Human Empathy: Understanding user sample sizes, empathy, psychology, evolution, game theory, etc.

Practical Spirit: Facts, data, observation, practice, trade-offs, feedback, iteration, and self-reflection.

3. Critical Thinking

Final Summary:

The user model and transaction model are the core of a PM's thinking.

The user model revolves around the customer experience, which includes stakeholders and the journey, and is a complex system. The product manager’s task is to iterate this model, understand its uncertainties, and gradually align it with real user behavior, making it more predictable. The model is crucial from the moment the product is perceived by users to the moment the value feedback is received, with the construction of the user’s psychological model being especially important.

The source of demand is the user, and its destination is also the user. Demand is discovered, and the path to handle that demand needs to be iterated or changed. A new path must be superior to the old path in terms of overall cost and be perceivable by users to be valuable enough to be used.

Enterprises exchange value with users through products. Transactions are exchanges of value that arise from relative value inequalities. To decide what to do and what kind of transaction to make, one must consider the utility of the product, supply and demand, costs, and margins. At the same time, it is important to ensure that users can obtain long-term value, making the transaction sustainable.

The value of an organization lies in its ability to share knowledge and manage the process of value creation more efficiently.