Explore how to develop user insights and enhance your product design by understanding user behavior, characteristics, and needs. Learn practical strategies to stay user-focused and create meaningful experiences that resonate. 📈✨

"User-centered" — this is a phrase most product managers hear when they first start, and it's what they're expected to focus on. Yet, in daily work, very few manage to fully implement this approach. The root of the problem lies in a lack of insight and understanding of users. In this article, let’s see how the author tackles this challenge.

For the past few years, I've been involved in product design aimed at both the market and users. Understanding users is a crucial part of my job.

As I've gained more years of experience, I've developed some of my own thoughts on user research, so I'd like to share them again in this article.

User Focus in Specialized Roles 💼

With the increasing segmentation of roles in the internet industry, some product roles may not require close attention to users, such as those in back-office or internal IT product management. Here, when we talk about "users," we are referring to products aimed at the market and user-facing services that require our focus.

1. Insight is Built on Understanding Users 🔍

When mentoring new colleagues, I noticed that some had a strong sense of insight and could immediately identify deeper issues.

We wondered if we could summarize a set of product methodologies to enhance the overall insight of our team.

However, after several rounds of one-on-one coaching and practice, we realized that insight is difficult to transfer.

It seems no matter how hard we try, one person’s insight can’t be simply learned by another. Even after we help someone understand a requirement and create a solution together, the next time the same issue arises, they may still be lost.

After team discussions, we concluded that insight is not easily replicable. It is not a quick-to-copy methodology, nor can it be taught through a few sessions. Insight reflects one’s understanding of users, and at its core, it is about cognitive awareness of users. This difference in understanding is what makes insight hard to replicate.

This is why, when we debate an issue and reach a point where we discuss the user’s intention or the context, our team leader will stop us — because cognitive differences cannot be resolved through debate.

In essence, those who possess insight hold the key to seizing market opportunities. So, insight is often a key indicator of a product manager’s abilities.

How can we improve insight? It depends on how deeply we understand users. Only by deeply understanding users can we truly discern their real needs in specific contexts and discover product opportunities.

To understand users, we need to maintain a beginner’s mindset day after day, researching their behaviors, characteristics, and scenarios. Users' characteristics are dynamic, so ongoing research is required to maintain a true understanding.

I’ve also seen high-level managers or experienced professionals make decisions that don’t align with user expectations. Over time, they become disconnected from users, losing sight of the core purpose of their product, and fail to understand the market and users.

Therefore, no matter your position or experience level, you must continue to study users, consistently and thoughtfully. Only by maintaining this attitude can insight become a core competitive advantage for product managers.

2. Studying User Characteristics 🤔

Users have many characteristics — different business backgrounds, roles, and scenarios. These diverse combinations can create thousands of user profiles. Here, let's discuss the fundamentals of users.

Users Are Humans 👥

Everyone has their own understanding of "users." Zhang Xiaolong said that users are essentially people. Yu Jun said users are an aggregation of needs, while others see users as data points.

I personally don't agree with treating users as abstract concepts. If we study users too abstractly, treating them as mere data points or concepts, we’ll eventually lose touch with their true nature. After years of product work, we might become desensitized to users, doing our jobs robotically, or designing products with no regard for users, solely driven by commercial motives.

When designing products, we need to remember that behind all these usage statistics are real people — individuals. We must approach user research with respect and reverence.

Lack of reverence leads to over-designing. Products that don’t respect users will be abandoned by them.

Thus, when studying users, we must treat them as real people, as vibrant, independent individuals.

Users Are Dual-Natured 🧠

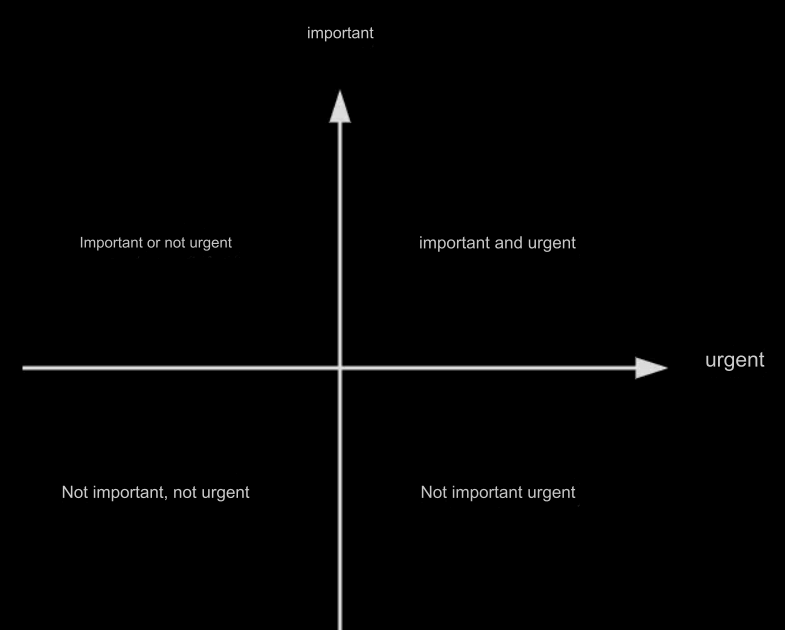

Humans are both animalistic and rational. The animal side refers to our primal instincts — greed, anger, stupidity, laziness, etc. It’s the survival mechanism that has kept us going for millennia. The rational side distinguishes us from animals, allowing us to think critically, make long-term decisions, and overcome short-term animalistic impulses.

Yet, when thinking, the animal response is faster than rational thought, as it has been honed over millions of years.

Thus, product designs that align with the animalistic nature of users often feel more comfortable. This is why many designs involve quick feedback loops — they satisfy the immediate impulses of users.

However, in modern society, animalistic instincts are not as beneficial for learning and growth. In our daily work and life, we need to control these instincts and use rational thinking to make better decisions.

Rational thinking, though slower, helps us make decisions that are beneficial in the long term, especially in design decisions.

For products that require persistence or self-control, guiding users’ animal instincts can make tasks more engaging. For example, games often provide instant feedback to reduce the learning curve.

Users Are Goal-Oriented 🎯

When we design products, we focus on users in specific contexts. A person’s needs vary depending on the situation. For example, while on the phone in an office, you don’t want the microphone to be too loud, but in a park with background noise, you need the volume higher to hear clearly.

So, studying users should always consider the specific context.

3. Becoming the User 🧑💻

Whether accepting requirements or understanding users, it’s difficult to fully grasp the real scenario without experiencing it firsthand.

I believe true empathy comes from walking in the users' shoes. For C-end products, this is relatively easier, but for B-end products, it’s more challenging, as they often require simulating real business operations.

For our B2B products, we initially relied solely on research. But we found it hard to understand the real business scenarios, so we invested in opening an actual store and rotated team members to run it.

Through hands-on involvement, we uncovered many unmet needs and made several product innovations that others missed.

4. Treating Users as True Friends 🤝

As product managers, we often unconsciously inject our own emotions and perceptions into products. Over time, the product starts reflecting the designer’s personality.

In the past, I designed more tool-oriented products, focusing only on efficiency. Later, my team leader asked me to add a simple weather forecast to the homepage, but I didn’t think it added much value.

However, my leader explained, “Your products are too tool-like. They lack warmth.” I didn’t understand this then, but later realized: without warmth, products are just tools — like holding a cold hammer. People will discard the hammer once something better comes along.

When we treat users as friends, infuse warmth into our designs, and genuinely care about them, users will feel it, and they’ll stick around.

5. User Value = Efficiency + Experience 🎯

User value consists of efficiency and experience.

Efficiency refers to faster workflows, improved productivity, or simplified processes. Experience involves emotional, interaction, and visual satisfaction.

Only by balancing both aspects can we design products that provide real value to users.