In the context of business transformation and market change, the leadership of middle managers is particularly crucial. This article delves into how middle managers can drive team and company growth in complex and dynamic environments by aligning with their superiors, unleashing the potential of employees, and fostering cross-departmental collaboration. It explores three key aspects: upward management, downward empowerment, and horizontal collaboration, ensuring organizations move forward steadily.

Manage upward, keep pace with superiors, and build trust; empower downward, help employees grow, and activate the team; horizontal collaboration is the key to winning battles, promoting relationships, and growing together.

A new round of market cycles is taking shape, and the internal and external living environment of enterprises has undergone profound changes. Looking outward, the new generation of information technology and manufacturing are deeply integrated, emerging industries are gradually rising, and artificial intelligence is reshaping thousands of industries; looking inward, the new organizational era has arrived, and the pyramid structure, strong target control, and heavy KPI assessment management model of many companies in the past are being replaced by flat organizations, matrix structures, and OKR models. We must adapt to changes in the external environment and keep up with internal organizational changes. In a complex and changing era, enterprises face greater uncertainty and need to adapt to new challenges. Among them, the role competence and leadership of middle-level managers are crucial.

However, many middle-level managers cannot keep up with the company's strategic development requirements in terms of role competence and leadership, and have problems such as weak business growth, loose team management, difficulty in improving performance, lack of innovation results, and slow talent training. There are seven typical manifestations: first, focusing on business management and neglecting team management; second, focusing on experience reuse and neglecting team innovation; third, focusing on performance results and neglecting process management; fourth, focusing on emotional management and neglecting system management; fifth, focusing on single-handed struggle and neglecting team collaboration; sixth, focusing on plan execution and neglecting strategic thinking; and seventh, focusing on living in the present and neglecting talent training. If the middle-level problems are not solved, it will be difficult for the company to break through. The cultivation and improvement of the leadership of middle-level managers should be carried out simultaneously from three aspects: upward management, downward empowerment, and horizontal collaboration.

Manage upward and resonate with superiors

Rosanne Badowski, executive assistant to Jack Welch, former chairman and CEO of General Electric, formally proposed the concept of "managing upward" in her book "Managing Upward: How to Establish Effective Relationships with Superiors". Rosena believes that management requires resources, and the right to allocate resources is generally in the hands of superiors. Therefore, if you want to obtain the resources needed for work, you need to manage upwards - to be precise, it is to obtain various resources to achieve goals through upward communication, and then achieve organizational performance. There are three collaborative strategies to achieve upward management.

1. Collaboration based on goals

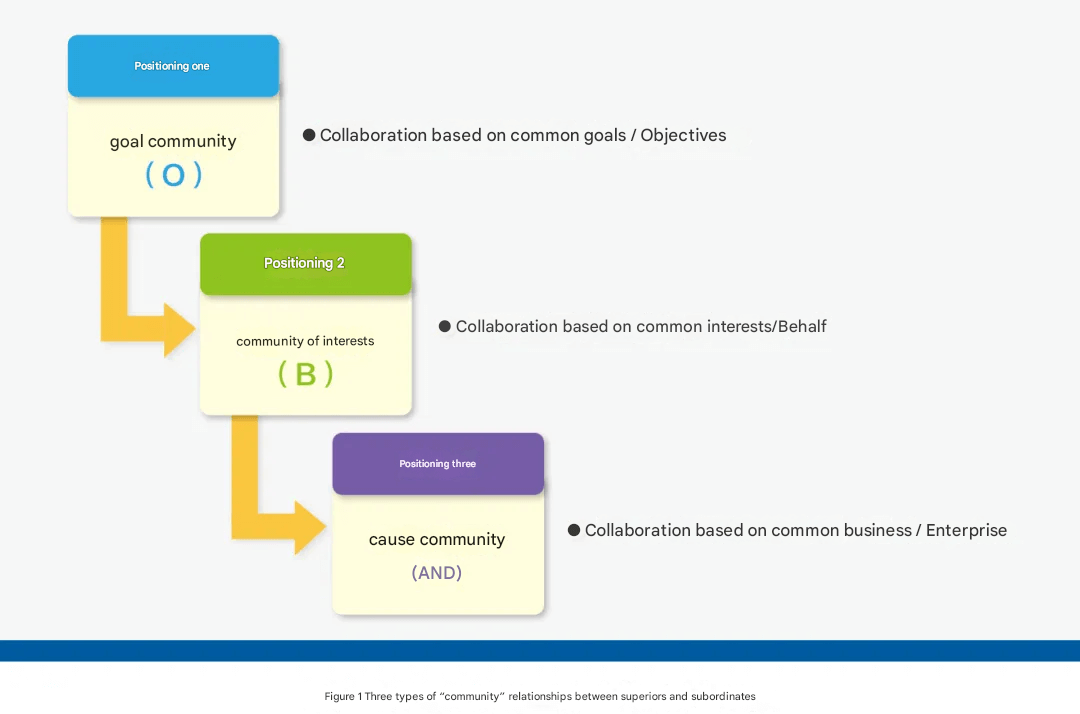

Superiors and subordinates are natural "goal communities, interest communities and career communities" (see Figure 1), but it does not mean that there are no differences between superiors and subordinates. This depends on the recognition of goals, as well as the needs, differences and variables involved in the goal-setting process. The goal-based collaboration between superiors and subordinates is to understand needs, reduce differences and reduce variables. Upward collaboration can be achieved from the following three dimensions.

First, understand the company's development stage and the main contradictions it faces from the company's goals. Enterprises usually go through the formation period, shock period, growth period, maturity period, and decline period. The goals to be achieved and the main contradictions faced by the enterprise in each stage are different. For example, in the formation period, the team has just been formed and has a weak sense of strategic direction. The so-called goal is actually to survive first; in the shock period, the team needs to run-in, which is prone to various differences and conflicts. At this time, trust needs to be built and team rules need to be formed. Middle-level managers understand the company's development stage and the original intention of the company to set strategic goals. Especially when there are disagreements between superiors and subordinates, middle-level managers can go back to the company's development stage and the main contradictions faced to solve the problem, which is more conducive to the resonance between superiors and subordinates.

Second, actively participate in the formulation and decomposition of company (superior) goals. It is normal for enterprises to decompose goals from top to bottom, but it does not prevent middle-level managers from participating. For example, by reviewing the work of departments or teams in the past year and giving feedback to superiors on experience and lessons, superiors can reflect on past strategic decisions from the execution level, adjust strategic directions and goals in the new year, and integrate strategy with execution; middle-level managers can also share their insights on company strategy with superiors, and make suggestions from the perspective of superiors and in combination with past business practices.

Many middle-level managers have a cognitive misunderstanding: "Formulating company strategic goals is the business of leaders and executives, and has nothing to do with themselves. As long as the tasks assigned by superiors are completed, they are qualified to point fingers at the goals of superiors." This is wrong. In fact, superiors also have cognitive blind spots and hope for more feedback. If middle-level managers can integrate their personal insights into the company's strategy and suggestions for their superiors' work into the formulation of their superiors' goals, it will not only help integrate the strategic execution of superiors and subordinates, but also make the understanding of the goals highly consistent from the source, and then achieve the same desire of superiors and subordinates.

The third is to let superiors understand the goals and key measures of their departments. Many middle-level managers believe that the goals are disassembled from the goals of superiors, and as long as they are consistent with the goals of superiors, their superiors don't care what they do. In fact, three situations should be distinguished: First, the management style of superiors. If superiors expect to know specific action plans and business details, middle-level managers need timely feedback and communication; second, the company's development stage, especially the start-up period of new business, the time from decision-making to execution correction is short, and the superiors and subordinates need to respond quickly and synchronize information at any time; third, the company's organizational form, the traditional pyramid structure and the flat organizational structure are completely different, which is related to the company's development stage (such as start-ups and century-old stores), and also to the business attributes (such as manufacturing and technology Internet industries). Different organizational forms have very different requirements for the granularity of goal decomposition between superiors and subordinates.

2. Communication based on trust

Without trust, how can we talk about upward coordination? Between superiors and subordinates, trust is the premise and coordination is the result. For middle-level managers, building trust upward has two meanings: one is how to make superiors trust themselves; the other is how to make themselves trust their superiors. The first level is easy to understand, but the second level is not easy to understand. Even many middle-level managers do not realize that they have trust problems with their superiors, which not only affects upward coordination, but also becomes an obstacle to organizational development. There are three most typical situations.

In the first case, middle-level managers "disobey" their superiors. There are roughly two reasons: one is that in terms of professional ability, they think that their superiors are not as good as themselves, or even think that they are "laymen leading experts". In this case, it is difficult for middle-level managers to accept their superiors from the heart. If this cognition is strengthened, it often leads to the extreme situation of "I oppose any proposal from my superiors", and the tension between superiors and subordinates can be imagined; secondly, at the level of values, middle-level managers who believe that some of their superiors' practices are inconsistent with their own values, or even believe that their superiors are completely wrong to do so, tend to "keep their distance" from their superiors, and there is no way for middle-level managers to trust their superiors.

In the second case, middle-level managers have conflicts with their superiors or misunderstandings of their superiors. It is normal for superiors and subordinates to have completely different views and solutions on a certain issue. However, if this disagreement turns into a conflict and confrontation between the two sides, or if middle-level managers choose to use temporary compromises to cover up their inner opposition, misunderstandings and barriers are likely to form. Over time, middle-level managers have deeper and deeper prejudices against their superiors, and daily communication is often superficial, with calm on the surface but turbulent in reality.

In the third case, it is caused by the inherent cognition or personality of middle-level managers. Some middle-level managers prefer business or technical work, are willing to work hard, and can lead the team to conquer cities and territories, but they are very passive in communicating with their superiors. They think that there is no need to report many things to their superiors - the superiors should know, or they insist on the way of doing things "If the superiors don't look for me, I can't bother the superiors", which increases the information asymmetry between superiors and subordinates. Some middle-level managers have an inherent perception from the beginning that "If you have nothing to do, you are either flattering your superiors or have bad intentions", and they will not communicate with their superiors except for the necessary communication. The consequence of this is that these middle-level managers are not clear about the background and starting point of their superiors' decisions, nor do they understand their superiors' role needs and preferences, and the superiors and subordinates are drifting further and further apart. On the other hand, if there is full trust between superiors and subordinates, the following performances will be observed: smooth communication and frequent exchanges between superiors and subordinates; speaking directly and openly, and communicating different opinions at any time; superiors fully authorize subordinates, subordinates give timely feedback to superiors, and processes and mechanisms operate well; business problems are solved in a timely manner, management risks are discovered in a timely manner, and no bottom-line mistakes are made; business innovation is continuous, performance is continuously improved, and talents continue to emerge.

3. Results-based execution

With goal-based collaboration and trust-based communication, middle-level managers ultimately need to return to the results level to verify the effect of upward collaboration. If superiors and subordinates can resonate with each other based on goals, trust each other, and communicate smoothly, but performance does not improve, this is obviously not normal. On the way to achieving results, middle-level managers often encounter several "roadblocks": First, resources are limited, not even temporarily limited, but always limited; second, team capabilities are lacking, and some middle-level managers will lament that team capabilities are never enough; third, plans cannot keep up with changes, and the deepest experience of some middle-level managers is that "plans may never keep up with changes."

Take the third "roadblock" as an example. Since it is normal that plans are not changing as fast as they should, how should middle managers deal with uncertainty and minimize the adverse effects of changes on the achievement of departmental goals? Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, proposed a five-step process for dealing with uncertainty: the first step is to clarify goals and plans; the second step is to find problems that hinder the implementation of action plans due to various uncertainties, and not to tolerate problems; the third step is to diagnose problems and find the root causes; the fourth step is to design solutions; the fifth step is to implement solutions, iterate continuously, and finally get results.

Empower downward to promote organizational change and evolution

Middle managers are generally familiar with team management, but not with team empowerment. Team empowerment refers to managers creating processes, mechanisms and cultural systems to activate greater initiative of front-line employees, and do everything possible to help employees improve their capabilities, so that they dare to innovate, take the initiative to explore, and take responsibility, thereby achieving a win-win situation for employees and companies. There are three strategies for middle managers to do a good job of team empowerment.

1. Strive for sustained growth

Team empowerment must of course serve department growth. Growth not only refers to performance growth, but also includes cost reduction in the production department, improved customer service department satisfaction, more partners in the channel department, more patents in the R&D department, and improved brand influence in the marketing department. These all fall within the scope of company growth. To achieve department growth, middle-level managers have three levers.

The first is customer demand. The key to growth is customer pay. If customers are not satisfied and do not pay, there is no growth, and team empowerment will become aimless self-entertainment. Customers include both "external customers" who usually pay for the company's products or services, and the various departments that are linked together in the company's value chain, namely "internal customers." For middle-level managers, there are usually three measures for team empowerment based on customer needs: First, through case studies and review, guide team members to pay attention to customer pain points and needs, combine key behavioral indicators with department KPIs, and directly link team members' interests with customer pain point resolution, customer satisfaction and other indicators; Second, through leading by example and demonstration effect, on issues involving customer pain points, customer service improvement, customer satisfaction improvement, etc., demonstrate to department members by speaking, holding meetings, discussing, stopping, and motivating; Third, learn to magnify key events, especially when encountering typical events that are ambiguous or have no clear standards, middle-level managers should point out the direction to team members through their own handling methods.

The second is process optimization. How to meet customer needs? In addition to product and service levels and employee professionalism, the key implementation path is process optimization. From the perspective of team empowerment, middle-level managers can do two things: First, lead department members to evaluate existing processes. This is part of coaching and improving employees' capabilities, such as helping employees understand the shortcomings of existing processes, what problems they will cause, and what impact they will have on customers; discussing with employees the problems encountered in department growth, and distinguishing which ones are caused by the process itself and which ones are caused by factors outside the process. Second, promote the determination and implementation of process optimization plans. Including what are the standards for process optimization, how to make decisions when encountering dilemmas, how to balance current project problems and department goals, how to resolve process conflicts with other departments, and what to do when new problems arise during the implementation of action plans. Promote process optimization through team co-creation.

Third, business innovation. Process optimization is more about solving the problem of "more, faster, better, and cheaper" at the efficiency level, while business innovation brings imagination to the department to double its performance. There are six practices for promoting departmental business innovation: First, provide team members with a series of training and related resources on business innovation, such as the latest industry cutting-edge information, technical reports, market trends, etc.; Second, build a departmental knowledge sharing system to encourage team members to actively share practical experience and promote the transfer of capabilities among team members; Third, form an innovation team to find innovative solutions for specific problems; Fourth, establish an innovation incentive mechanism to allow employees with innovative ideas and practices to become benchmarks and receive rewards; Fifth, build an innovative culture, establish a fault-tolerant mechanism, and reduce the innovation burden of employees; Sixth, break the limitations of departments, cross-departmental and cross-team innovation collaboration, and jointly tackle key problems with external institutions and upstream and downstream partners to make the company's internal and external resources work for me.

2. Promote team evolution

Business growth depends on the team. Without the continuous evolution of team capabilities, no matter how great the strategic goals are, they are castles in the air. One of the results of team empowerment is to help team members evolve continuously. Middle-level managers also have three handles to promote team evolution.

The first is goal traction. Whether it is external pressure or internal motivation, using goals as traction can better help employees evolve. The "goals" mentioned here are not only the organizational goals that managers want, but also the personal goals of employees. To achieve goal traction, the best way is to let KPI reflect the combination of departmental goals and personal goals of team members. However, the focus is not on the KPI itself, but on the communication before KPI setting. For example, middle-level managers should review the business results of the previous year with team members, find gaps and key opportunities, and then discuss the goal setting and KPI of the department in combination with the company's annual strategic goals. But this is far from enough. Middle-level managers need to work with the team to dismantle the path and key action measures to achieve the goal, find the main obstacles that affect the achievement of the goal, and take inventory of resources and solutions inside and outside the department. KPI communication cannot be turned into instructions. At the same time, middle-level managers also need to understand the career planning of employees, especially their personal goals and demands for the next year, and analyze the relationship between departmental goals and personal goals with them, how achieving KPI will help achieve personal goals, what support the department will provide, and what cases or experiences can be used for reference. Only through this communication can departmental goals be truly combined with personal goals of team members to achieve goal traction.

The second is talent inventory. Goal traction is to solve the problem of team member advancement from the business level, and regular talent inventory is to adjust and correct from the level of department member structure, effectively improving the level of team member advancement. Talent inventory is generally divided into four steps: the first step is to return to the department's strategic goals and current management pain points, and determine the standards, goals, processes, tools, outputs, etc. of the talent inventory. Middle-level managers also need to communicate with their superiors to ensure that the talent inventory is in line with the company's development strategy; the second step is to conduct talent assessment based on the standards, and select different assessment tools for talent assessment and feedback based on the actual situation of the department; the third step is to hold a talent calibration meeting and convene relevant personnel to discuss the assessment process and results.

In-depth communication and discussion, exchange and reach consensus on the subsequent differentiated talent training plan; the fourth step is to input the results, implement the differentiated training plan for different team members, and adopt action measures including PIP (Performance Improvement Plan) to implement the results of the talent inventory.

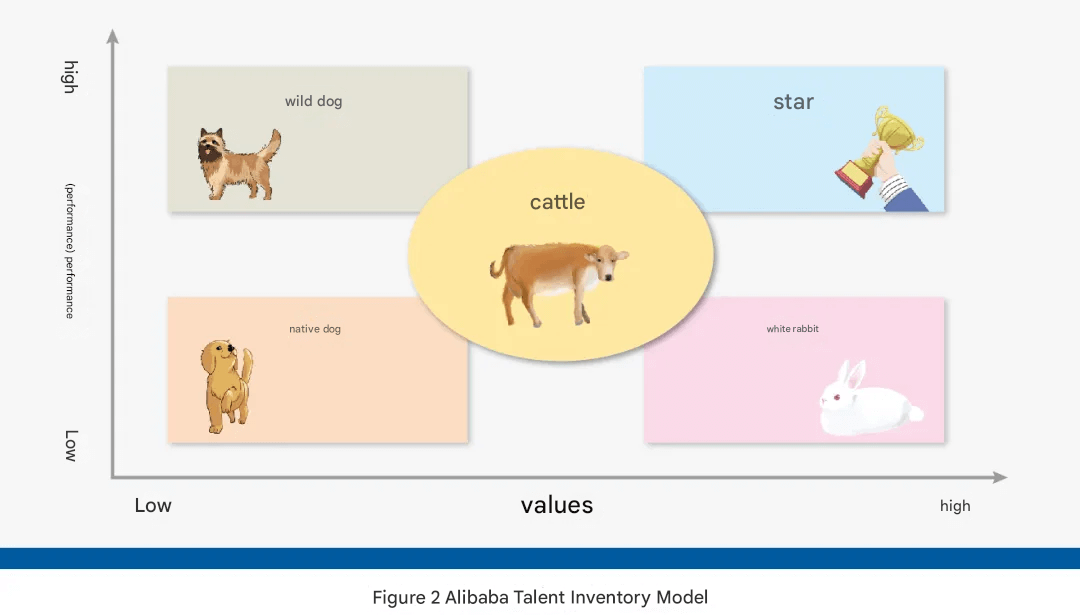

Inventory is not the goal, team evolution is the key. Therefore, after completing the talent inventory, middle-level managers should formulate corresponding empowerment strategies based on the talent inventory. Taking Alibaba's talent inventory as an example, it chose the "(performance) performance-value" evaluation combination, but the processing method is different from other companies. Alibaba calls employees with both excellent performance and values "stars". Such employees will become the benchmark of the team, and they will be promoted, given salary increases, and trained with emphasis, and various empowerment measures are indispensable. Alibaba calls employees with poor performance and low value evaluation "local dogs" and eliminates them without hesitation. Alibaba calls employees with good performance but low value evaluation "wild dogs" and eliminates them without hesitation. Alibaba calls employees with good performance but low value evaluation "white rabbits" (some are "old white rabbits") who often disregard the interests and values of the company in order to achieve their goals. Alibaba calls such employees "white rabbits" (some are "old white rabbits"), and generally helps them improve their performance through empowerment. If various empowerment measures are ineffective, they will say goodbye early. There is also a type of employee whose performance and value evaluation are in the middle but not outstanding. Alibaba calls them "scalpers". For such employees, we must first analyze the reasons for the gap between them and star employees, whether the empowerment measures are wrong or their cognition and methods are problematic, and then help them improve and upgrade in a targeted manner (see Figure 2). Alibaba's team empowerment approach based on employee differentiation can better help department members evolve. "Today's highest performance is tomorrow's minimum requirement", this value may be the best annotation for Alibaba's team evolution.

The third is echelon construction. The value of echelon construction to organizational development is self-evident. From the perspective of team empowerment, to do a good job in departmental echelon construction, middle-level managers need to do three things. First, select the "seeds". Who are the core talents of the echelon? There are three standards: strategic standards, that is, talents that meet the company's future strategy; performance standards, which include both current performance and employees' future performance potential; culture and value standards. If the "seeds" do not meet the company's culture and value requirements, or even past behavior is contrary to them, they are poisonous "seeds" and will bring greater risks to the organization. Second, cultivate "soil". With good "seeds", of course, good "soil" is needed. Good "soil" refers to a fair selection mechanism, a perfect training system, and a positive evolutionary environment, which are crucial for the thriving growth of echelon talents. Third, actual combat testing. How good the "seeds" are, practice has the final say. Middle-level managers must admit that they have also made mistakes, and need to return to the market perspective and actual combat perspective to test the results of echelon talent training through actual combat.

3. Promote organizational change

Continuous growth solves the problem of standards and evaluation of team empowerment, talent inventory solves the problem of differentiation and personalization of team empowerment, and organizational change clears system obstacles for team empowerment from the level of department mechanism, culture and platform, helps middle-level managers fully activate individual employees, and continuously improve department performance. John Kotter, the father of change management and professor at Harvard Business School, has developed the "Eight-Step Change Method", which can be used as a route guide for middle-level managers to carry out team change. The first step is to create a sense of urgency. The first step of change is not to let department members immediately engage in vigorous change actions, but to create a sense of urgency for department change first. The second step is to form a change vanguard. Department change is not a solitary battle, nor is it a "one-man battle". For organizational change to succeed, it must take the mass line. The third step is to create and share a vision. For an organization, the most difficult thing is not to create a vision for change, but to enable team members to share the vision for change. Department change is not a "solo dance" for middle-level managers. The fourth step is to convey and repeat the vision. Let all team members know the vision and participate in department change. The fifth step is to clear obstacles to change. For middle-level managers, the real challenge is that change is blocked, and obstacles must be removed to smoothly promote change. Step 6: Accumulate small victories. One small victory after another can motivate team morale. Nothing can boost the confidence of department members in change more than "frequent good news". Step 7: Consolidate achievements and deepen change. Summarize experience and lessons based on small victories, and challenge the "hard bones" that affect department change. Step 8: Mechanize the results of change. Summarize change experience, consolidate excellent practices, reuse benchmark talents, and precipitate typical behaviors and cases into culture and values. Only in this way can the change be called fruitful and a dynamic team empowerment.

Horizontal collaboration to promote cross-departmental cooperation

Finally, it comes to "Lao Wang next door" (same level/cross-department). Upward management and downward empowerment, there is a superior-subordinate relationship between the two parties, and the relationship of appointment, reporting, assessment, authorization, etc. is clear, but the middle-level managers of the same level department may belong to the same superior or to different superiors. For group companies with subsidiaries, divisions, and regional operation centers, there is not only "Lao Wang next door", but also "remote Lao Wang", "Lao Wang who has never met", "Lao Wang with completely different positions", etc. In this case, if middle-level managers want to promote project implementation and obtain cross-departmental support, one unavoidable question is: how to better promote cross-departmental collaboration? There are three key points.

1. Winning the battle based on project success

In cross-departmental collaboration, winning the battle is an incentive for the parties involved: it can prove that the middle-level managers and "Lao Wang next door" have reached a collaborative result, and the efforts of both parties have not been in vain; it can also prove that the collaboration method is correct and both parties are the best CP (partners) of the company. On the other hand, even if the middle-level managers and "Lao Wang next door" have a good relationship, there are no differences and conflicts, and the two sides have reached a high degree of consensus, but they always lose the battle, it won't take long for the middle-level managers and "Lao Wang next door" to collapse in mentality, how can we continue to collaborate?

Another key word is common goal. Winning the battle based on common goals must be a win-win situation, the differences between departments are easy to resolve, and cross-departmental collaboration is easy to bear fruitful results. The most typical scenario of winning a battle is to achieve continuous project success. This includes both projects in the context of project management and key tasks or special tasks of the company. Achieving success at the project level is an important criterion for evaluating the effectiveness of cross-departmental collaboration.

2. Promoting relationships based on business linkage

There are three relationships between departments, namely business relationships, team relationships and strategic synergy relationships. Taking business relationships as an example, there are three key indicators for evaluating the level of business linkage between departments: response time, collaboration efficiency, and satisfaction evaluation. The satisfaction evaluation of cross-departmental collaboration often adopts a cross-scoring method, and continuously improves the level of business linkage of each department through continuous feedback and evaluation.

In addition to direct business linkage, at the team relationship level, cross-departmental collaboration can do three things: First, through cross-departmental team-building activities, enhance mutual understanding among department members. The more contacts the parties have, the more they can understand each other's motivations and starting points. With mutual understanding, there will be empathy. When there are disagreements or conflicts in cross-departmental collaboration, it is easier for the parties to find solutions. Second, by jointly organizing business training or theme sharing activities, more opportunities for contact and communication can be created for team members, which can greatly reduce the communication costs between departments. Third, a collective memory between departments is formed, such as the anniversary of a certain project, collective honor medals, certificates, etc. Especially for project closing meetings, there should be a sense of ceremony and "unforgettable moments". On the basis of business collaboration, the emotional connection between people (trust, resonance, identity, etc.) has always been the glue for improving team relationships between departments.

3. Grow together based on strategic collaboration

The first two strategies, whether based on project success or business linkage, focus on the present, that is, the practical problems encountered in the process of cross-departmental collaboration. Middle-level managers should improve the level of cross-departmental collaboration, not just limited to the present, but also return to the company's goals and strategic collaboration level, and jointly promote the implementation of the company's strategy through departmental performance growth and team capacity building. How to carry out cross-departmental collaboration based on company strategic collaboration? Middle-level managers should do a good job of three collaborations.

The first is strategic coordination based on the KPI system. The most common way for departments to undertake the company's strategic goals is the KPI system. Through the strategy map, the company's goals are broken down into the goals and "must-win battles" (key action measures at the company's strategic level) of each business unit and the middle and back-end departments; through the balanced scorecard (BSC), the company's strategy is broken down into KPIs in four dimensions: finance, customers, internal operations, and learning and growth, and then a comprehensive performance appraisal system is formed.

For example, if the company's annual strategic theme is "regional market expansion", then the KPIs of each department will inevitably point to this theme, and "regional market expansion" has become the biggest strategic consensus among departments. It's just that the KPIs of each department are based on their own professional division of labor. Some departments' KPIs pursue the speed of regional market expansion (such as the number of new stores, the number of franchisees, the market growth rate, etc.), some departments' KPIs pursue the effect of regional market expansion (such as per capita consumption of new customers, single-store profits of new stores, effective conversion rate of market activities, etc.), and some departments' KPIs pursue the cost efficiency of regional market expansion (such as input-output ratio, labor efficiency ratio, etc.).

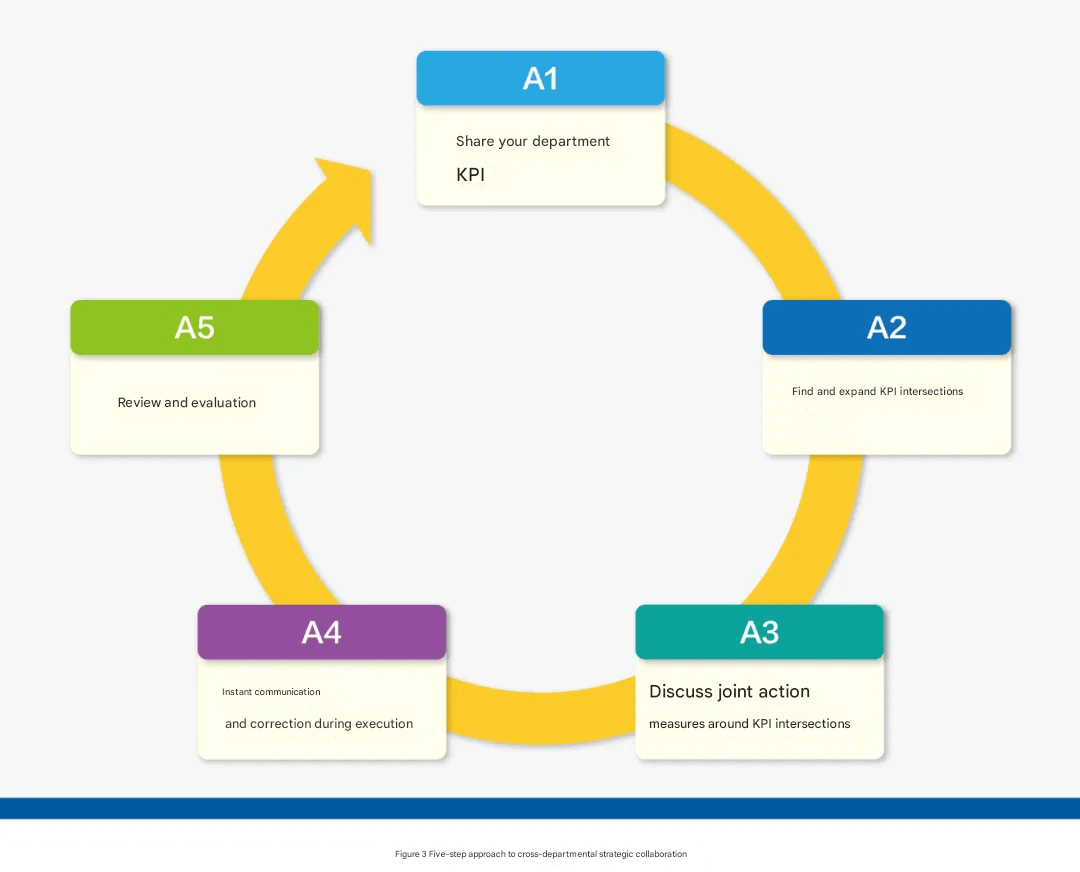

Therefore, once the strategy is implemented at the departmental KPI level, the phenomenon of "fighting" is inevitable: if you want speed, it is difficult to ensure quality; if you want quality, you must increase costs; if you increase costs, it is difficult to make profits; if you want to ensure profits, you must have speed; if you want speed, it is difficult to ensure quality. After going around in a circle, we are back to the starting point. To reduce the phenomenon of KPI "fighting" and promote strategic collaboration between departments, the best way is to find the intersection of KPIs, promote strategic collaboration based on the intersection of KPIs, and achieve the company's strategic goals together. There are five key actions in this approach (see Figure 3).

First, share the KPIs of each department. Sharing is not simply throwing a KPI table to the same-level department. Middle-level managers should share the background of the department's KPI setting, the implementation path, and the challenges that may be encountered with other departments, and seek the opinions of other departments.

Second, find and expand the intersection of KPIs. When the KPIs of each department and the challenges, obstacles, resource constraints, path measures and other elements that may be encountered in the process of achieving KPIs are brought together, the initial intersection of KPIs of each department appears. On this basis, through multiple communications, find ways to expand the intersection area. The larger the intersection area of KPI, the more common interests there are between departments; the area where multiple departments have KPI intersections is precisely the focus of the company's annual strategic collaboration.

Third, discuss joint action plans around the intersection of KPIs. Finding the intersection of KPIs only clarifies the common interests between departments, but this does not necessarily lead to cross-departmental strategic collaboration results. Only by formulating specific action measures around the intersection of KPIs, especially the key battles in which departments launch joint actions, can cross-departmental strategic collaboration come to fruition.

Fourth, instant communication and correction during execution. To ensure that all departments are in step with each other during execution, rather than acting independently, the cross-departmental communication mechanism needs to be effective, including daily periodic communication, communication at key nodes of joint projects, instant communication in emergencies, special communication on major issues, and so on. Communication is a form, and correction and getting cross-departmental collaboration back on track is the purpose. Don't wait until the problem is serious before reacting and regretting: "No, it shouldn't be like this, wasn't it agreed a long time ago?" Not only will it not help, it will also affect the resolution of the problem. It's better to communicate more in normal times than to "put out fires" afterwards.

Fifth, review and evaluation. At the end of the year or the beginning of the next year or the end of the company's fiscal year, each department can evaluate the completion of the cross-departmental KPI intersection through annual review and examine the behavior of each department in the annual strategic collaboration process. Departments can score and evaluate each other, or invite superiors, other departments, suppliers, and external partners to evaluate. The original intention of the evaluation is not to score itself, but to see "how others see themselves" through scoring. On this basis, each department must also systematically summarize the lessons learned in strategic collaboration, form a new methodology, and negotiate based on the KPI intersection of the new year to enter the next strategic collaboration cycle.

The second is strategic collaboration based on the company's "annual hard battle". "Hard battle" was originally a military term, and "annual hard battle" specifically refers to the company-level key tasks, projects or action plans that need to be completed within the year in order to achieve the company's strategic goals. How to conduct strategic collaboration on the "annual hard battle" between departments, there are four actions for middle-level managers.

First, clarify the goals of the "annual hard battle" and reach a consensus. Sharpening the knife does not delay the chopping of wood. Spending more time to reach a consensus is better than repeated communication and buck-passing during the execution process. The consensus that relevant departments (including executives who take the lead in promoting the "hard battle" at the company level) need to reach on the "annual hard battle" includes: why there is this "hard battle", what is the company's strategic original intention, what indicators are used to measure the "hard battle", what problems will be encountered in winning the "hard battle", what resources are needed, and what resource gaps are there.

Second, discuss key action measures based on consensus, select responsible persons and make written commitments. Consensus is only the starting point, and winning the "hard battle" is the key. All parties need to discuss key action measures based on consensus, and implement them to relevant departments, positions and responsible persons in the form of specific projects or tasks. Many companies often use "business responsibility statements" or personal performance contracts (PPC) to convert projects or tasks into written commitments, which can better promote strategic collaboration among departments at the implementation level of the "annual hard battle".

Third, communicate regularly, review the execution of projects or tasks, and make timely adjustments and corrections. When entering the execution phase, various unexpected and emergencies often occur, and the real test of cross-departmental collaboration has just begun. At this time, regularly organizing joint meetings of all parties in the project, information sharing and real-time communication mechanisms for emergencies, and instant communication and feedback with direct executives will help to quickly correct deviations, form new project consensus, and promote the achievement of "hard battle" goals.

Fourth, review and summarize, share responsibilities, and share results. In addition to summarizing the lessons learned from the "hard battle", all parties must return to the company's strategic level to measure whether the results of the "hard battle" are in line with the company's strategic original intention. For example, some "annual hard battle" companies not only want to achieve business results, but also hope to verify new business models, form new process mechanisms, train teams, and cultivate reserve talents.

The third is strategic collaboration based on business innovation capabilities. In addition to the right time and place, a company has its own core capabilities to achieve strategic breakthroughs, and the most important of these is business innovation. To promote strategic collaboration between departments based on business innovation, three key points should be grasped.

First, based on the company's strategy, focus on the business pain points that affect the company's development. The original intention of business innovation is to solve the company's business pain points, such as customer dissatisfaction, high costs, low efficiency, redundant processes, declining growth, performance ceilings, backward business models, and weak competitiveness. Cross-departmental collaboration based on business pain points needs to return to the company's strategic goals and development stages, and select the most urgent business pain points based on strategic priorities.

Second, small incisions, rapid verification, and continuous iteration. Cross-departmental business innovation faces three challenges: First, it is necessary to face failure, and the probability of failure is very high; second, it is necessary to face differences among all parties. Even if the business innovation goals are consistent, it does not mean that the positions of all parties are consistent at each node; third, various variables inside and outside the company, including company strategy adjustments, changes in customer needs, industry competition, internal organizational changes, etc., many cross-departmental business innovation projects will also face the risk of being abandoned halfway. Facing failure, differences among all parties and various variables, this huge uncertainty makes all parties involved lack a sense of security. To solve this problem, start with a small incision on which all parties can reach a consensus. A small incision refers to a business innovation point that all parties involved agree on, is easy to promote, and is easy to see results. Why start with a small incision? The reason is simple, it is easy to achieve, quick results, and can boost morale and enhance the confidence of all parties in promoting business innovation.

Third, the management mechanism of the innovation project team. Cross-departmental business innovation is often implemented by the joint establishment of an innovation project team by all parties. The management mechanism and operation model of the innovation team will directly determine whether the business innovation goals can be achieved. In short, by winning battles based on successful projects, promoting relationships based on business linkage, and growing together based on strategic collaboration, middle-level managers can better promote cross-departmental collaboration, making it possible to align top and bottom and connect left and right, and ultimately achieve unity of effort.