Project management is not only an essential skill for product managers but also for operations. This article summarizes five project management skills that are crucial for anyone working in operations, hoping to inspire you.

If I had to name the most valuable certificate I earned in my first five years, it would undoubtedly be the PMP Project Management Certification. Its significance lies not in the value of the certificate itself but in the five important management skills it taught me, which helped me step up from the execution level.

How to effectively delegate blame & prevent being blamed

How to achieve delivery

How to manage upwards

How to communicate within a team

How to close a project perfectly

Project management should not only be a mandatory course for product managers but also an important skill that operations professionals must master! Below are the five key project management skills every operations professional should know.

Skill 1: Delegation = Freeing Up Resources

The first step in mastering project management—delegation = freeing up resources!

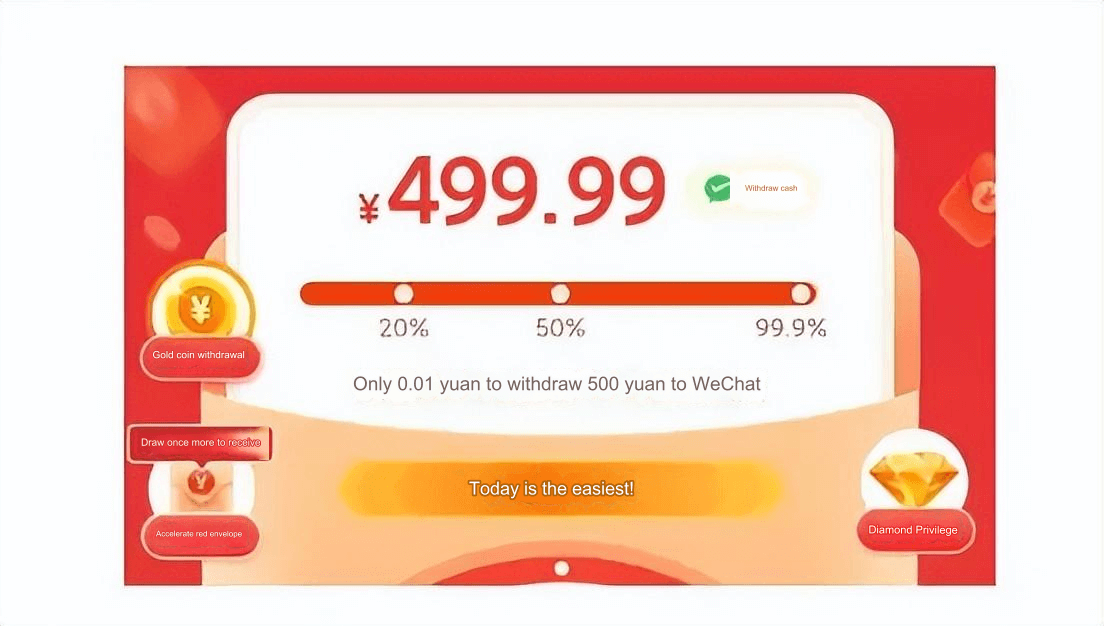

A project without adequate resources is like a marriage without a certificate or a promotion without a pay raise! If your boss verbally commits to a project but doesn’t provide sufficient manpower or resources, that project is as good as nonexistent! Reject empty promises, and start by identifying available resources.

Similarly, as a savvy professional, you should always observe and identify which core projects your company's resources are focused on. Getting involved in those projects early on is the first step to advancing in your career!

Skill 2: Define Project Scope and Goals

A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. The purpose of carrying out a project is to achieve the desired outcome through deliverables.

Therefore, before starting a project, make sure to clarify the following concepts and ask these key questions:

What are the goals the project aims to achieve?

What are the quantifiable deliverables and boundaries of the project?

What is the purpose of starting this project?

Once these questions are clearly and definitively answered, document everything and circulate it to the relevant parties. At this point, the first step in establishing the project charter is complete. A basic project charter should include the following information:

Project name

Project background

Project objectives

Project scope

Project timeline (start and end dates)

Project participants (resources)

Project milestones

Having a documented project charter can help you avoid complications, such as:

At the start, Boss A says the key feature was not highlighted, even though it wasn’t a target.

Midway through, Boss B wants to add a feature that could delay the project.

Near the end, Boss C says the outcome isn’t what they envisioned and accuses you of not following directions.

When these scenarios occur, you can confidently show them the project charter—this is what we agreed on! The core is having a documented project charter that you emailed to everyone.

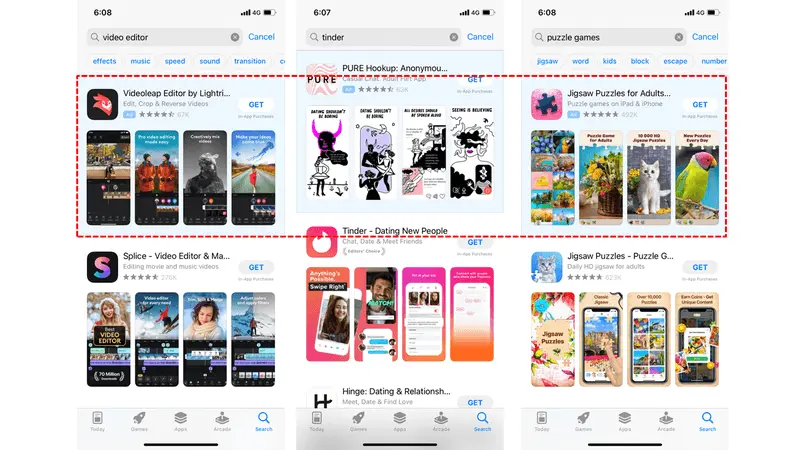

Skill 3: Stakeholder Identification = The First Step in Reducing Risk

Have you ever encountered these situations?

Halfway through writing an article, a colleague from the product team says the feature description is incorrect?

Right after release, a colleague from the branding team says the latest logo wasn’t used, and it must be retracted?

As a feature is about to be delivered, legal says it violates privacy laws and must be delayed?

These types of issues frequently occur, and one major reason is the failure to identify stakeholders at the beginning of the project.

Stakeholder identification can be done in various ways. The best way is to ask your supervisor—“Who do I need to inform about this?” If your supervisor isn’t reliable, ask your team members and hold multiple meetings to invite potential stakeholders.

Sometimes, a seemingly insignificant stakeholder might be the key to your project’s success or failure. Therefore, don’t overlook any potential risks, and consult with your colleagues. Letting major stakeholders know what you’re working on is crucial. If something goes wrong later, it becomes a shared issue, not just your personal failure.

Skill 4: Monitoring and Delivery Are the Core of Project Management

A project manager doesn’t necessarily need to do the actual work—and yes, you may have noticed that your boss doesn’t seem to do much. In practice, project managers don’t need to participate in execution, but they are responsible for the delivery.

In other words, if the project succeeds, the project manager gets the credit; if it fails, the project manager takes the blame. So, if you want to get promoted, you should actively take the lead in projects and become the project manager because, in the end, everyone remembers the project manager. The number of people you bring into the project and how many benefit from it reflect your competence as a project manager.

But having more credit doesn’t mean being a project manager is easy. On the contrary, the difficulty lies in that while you don’t participate in execution, you are responsible for the results. Managing leadership communication, monitoring progress, resolving resource conflicts, and dealing with absent key members—these issues alone can be overwhelming.

Thus, monitoring is a key tool in project management, and delivery is at its core.

Skill 5: Closing a Project Is as Important as Starting One

A project charter is crucial at the start of a project, but the final project report is just as important at the end.

A well-prepared closing report can serve several purposes:

Formally deliver results (No more questions—my job is done)

Highlight your achievements in a formal setting (Look at my contribution, oops, I mean everyone’s hard work!)

Include data in your year-end report (Oh no, I still need January’s project data for my year-end summary)

Document lessons learned (The new hire keeps asking what happened—let them read the documentation)

Provide follow-up instructions (The SOP is here—if something goes wrong, check the document before coming to me)

A good closing report should include the following sections:

Project Background and Objectives: Briefly introduce the project, including its origin, purpose, scope, and expected outcomes.

Execution Process: Summarize the project execution, covering planning, resource allocation, task assignment, progress control, and risk management.

Results and Highlights: Detail the project’s results and key achievements, as well as innovations, lessons learned, etc.

Challenges and Solutions: Analyze challenges such as delays or cost overruns and provide solutions or improvements.

Lessons Learned: Summarize key lessons from management, technical, and team collaboration aspects.

Project Evaluation and Summary: Evaluate the project’s success, shortcomings, risks, and its impact on the organization.

Suggestions and Improvements: Offer recommendations to improve future projects.

Project Attachments: Include important documents, reports, and data for reference.

Project management is now a vital soft skill for many positions. In supply chain management, project management can be so complex that entire roles are dedicated to it. Meanwhile, in the internet industry, product managers often handle project management tasks, which is why product managers tend to have higher salaries.

Being a project manager isn’t easy—fighting for resources is an essential skill. The key to obtaining resources is whether you can convince leaders and departments to invest in the project and, once you have the resources, if you can successfully complete the project. Strong mental resilience is required to thrive in project management.

For those in regular positions, mastering these project management skills can help shift your perspective. Even if you can’t get promoted internally, you can frame your experience in a way that makes you more attractive when applying for new jobs.