In recent years, “circle” products have emerged in a constant stream. The concept of the "circle" has shifted from aggregating content to aggregating people. What is worth reflecting on in this transformation? This article explores the broader potential of “circles,” broadening its scope, and delves into the value and opportunities by analyzing its forms and characteristics.

The concept of the “circle” has been frequently mentioned in social products over the past year, and many interpretations have already emerged. As a practitioner in the social product field, I’d like to share my thoughts, hoping they provide some value.

This article is divided into two main sections: the first discusses the concept of the "circle," and the second focuses on the "circle" as a product.

The reason for this division is that most current interpretations of circles have already pre-assumed that the circle is just a “group” structure. However, in reality, circles have much more potential. The first section explores what the "circle" is and what potential product spaces it could occupy, while the second discusses the characteristics of the product forms commonly referred to as "circle" products.

1. The Concept of "Circle"

A "circle" is a group that shares a common dependency, including content dependency, communication dependency, emotional dependency, and so on.

Let’s assume this definition is correct, and I’ll continue explaining. If it holds up logically, it can be considered a valuable point of view.

With this definition, many common products today are "circles" — for example, "subscription accounts," "QQ groups," "chat rooms," "forums," and so on.

However, they have many apparent differences, such as different relationship structures: Subscription accounts are highly centralized, while forums and QQ groups are very decentralized.

Moreover, there are differences in content: subscription accounts are very content-heavy, whereas QQ groups are much lighter.

These apparent differences actually reflect one underlying reason: the differences in the people who make up these circles.

So, let’s examine the concept of “circle” from the perspective of people:

2. Forms of "Circle" Products

A "circle" is formed by people gathering around common characteristics, but each person’s level of “identification” with these shared traits varies.

For each individual, as they progress from “not understanding” to “loyalty” to common characteristics, their needs for information, emotion, and other aspects evolve. For the circle as a group, the accumulation of individual experiences eventually leads to a qualitative change in the group. This results in different stages of a circle, which are reflected in the different product forms.

1. Potential Circles

A potential circle is a group that exists in a "statistical sense." For example, “men on Weibo,” or “mothers on Xiaohongshu.” They are scattered around the internet, occasionally meeting to have fragmented discussions.

They don’t have stable social relationships or a consistent mode of interaction, and this is not yet a circle — but it is a prerequisite for one.

Typical product: Facebook before it had Groups.

2. Content Circle (Content Aggregates People, People Gain Content)

Among the potential circle, there are a few individuals who are more strongly aligned with the common traits: Some of them, as passionate sharers, become opinion leaders, broadcasting their love for these shared characteristics to those around them (like Xiaohongshu influencers). The people who share these traits gather around the opinion leaders, cheering them on, and form a content circle around them.

Typical products: WeChat subscription accounts, Weibo, various vertical media, Medium.

3. Community Circle (Community Shapes People, People Gain Recognition)

Gradually, more and more people discover their identification with these common characteristics and feel a strong desire for mutual recognition. To gain recognition, they must engage in more communication.

Their interactions influence their consciousness, and their collective consciousness in turn affects their communication — this collective awareness becomes the “group consciousness,” and their communication forms the “group norms.”

They start to become more alike — they want the same things, say the same things, and do the same things. 10,000 people can act as one. They are no longer addressed by their individual names, but referred to as “this group” (such as JRs). This is the community circle.

Typical products: Tieba, Hupu, Zhihu, Bilibili.

4. Social Circle (Social Encourages People, People Achieve Self-Satisfaction)

People are always looking for others who are most similar to them.

The community circle gradually becomes more segmented. As the group shrinks, the similarity among its members grows. When the similarity surpasses that of acquaintances, the community circle transforms into a social circle.

In the community circle, individuals must work hard to shape a personal image to fit into the group. In the social circle, everyone is so similar that there’s no need for personal branding. At this point, people can express themselves freely — they don’t need to worry about their peers rejecting them, because everyone understands them.

Typical products: WeChat groups (acquaintance-based relationships).

5. Summary

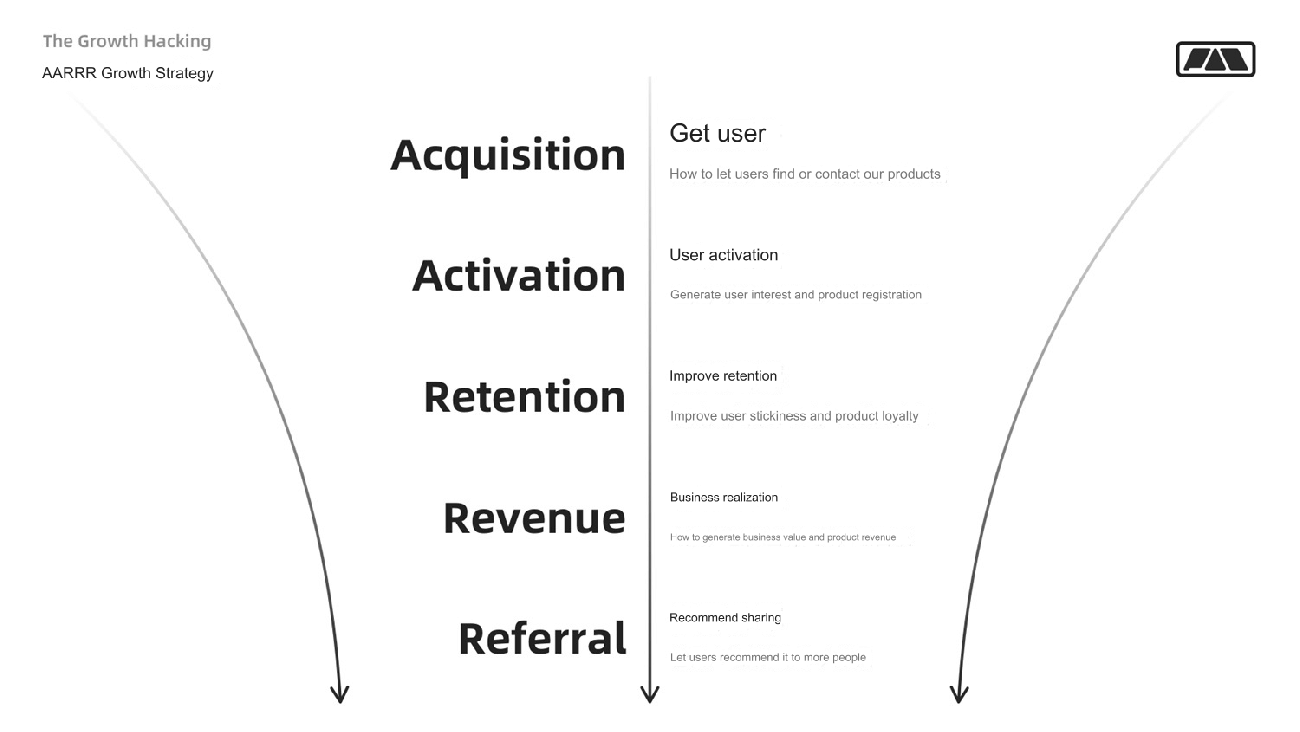

For each individual user, the journey from a potential circle to a social circle is a process of moving from “being unaware of what they like,” to “knowing what they like,” then to “seeking recognition,” and ultimately to “understanding oneself and expressing freely.” This process also mirrors the progression of needs from low to high.

For the circle as a group, each individual’s process of self-discovery brings changes to the entire group: from content consumption to communication and interaction, to cultural and emotional care — this is the more valuable evolution of the circle.

On the other hand, no product form is absolute, and there’s often a gray area. It depends on how the users use the product.

For example, for users who are only interested in content, Zhihu might be a “content circle”; for those who engage in genuine communication and sharing, Zhihu is more of a “community circle.”

3. Differences Between Various Circles

The article mentioned three forms of circle products earlier, and now let's discuss their product differences.

Since they are all information-sharing groups, the core differences lie in “who they communicate with” (social relationships), “what they communicate about” (content carrier), and “why they communicate” (core value). Let’s explore these three aspects:

1. Who They Communicate With (Social Relationships)

One center → Multiple levels → Equal communication

In a content circle, there’s a large gap in the understanding of common traits between the opinion leader and the members. Only the opinion leader’s opinions are valued. As a result, members only follow the opinion leader, and there’s no significant relationship between members, making the information flow highly centralized (opinion leader → members).

In a community circle, members’ understanding of common traits is more balanced, although differences still exist. They’ve achieved varying degrees of recognition and have formed multiple social layers (e.g., admins → stars → members → newcomers). The opinions of users at higher levels hold more value and dominate the information flow, which flows from the top tier to the lower tiers (e.g., in Xiaohongshu, influencers communicate via articles, while newcomers interact through comments).

In a social circle, everyone shares a similar understanding of common traits, and their opinions hold equal value. Therefore, both status and communication are equal.

Underlying logic: The value of user information determines social relationships.

2. What They Communicate About (Content Carrier)

Articles → Posts → Instant Messaging

In a content circle, members’ identification with common traits is still insufficient, so their need for information is not very strong. The only content producers, the opinion leaders, can only attract users by producing highly valuable, general content, typically articles.

In a community circle, members’ identification with common traits is stronger — they are willing to digest more fragmented content and are looking for more diverse information. Articles are no longer sufficient to meet their needs; fragmented, varied discussions are more helpful for addressing the various scenarios of the shared traits. As a result, posts become the dominant content carrier in community circles.

In a social circle, members’ identification with common traits is even higher, and they are willing to consume any content within the circle because they resonate with everything. For them, the circle is not only about shared traits but also about life and emotions. Therefore, instant messaging tools become the main form of communication in social circles.

Underlying logic: User information needs determine the content carrier.

3. Why They Communicate (Core Value)

Opinion leaders → Atmosphere → Emotional connection

In a content circle, the sole communicators are opinion leaders, whose loyalty stems from their followers’ admiration. While opinion leaders may temporarily dictate the survival of the content circle, the long-term existence of the circle is determined by the consumers who support it. Even if one opinion leader fades, a new one will emerge. Thus, the entry barriers to content circles are lower. However, once the circle matures, it becomes hard to disrupt due to the loyalty of its users (e.g., even after influencers leave Douyin or Huya, the platforms remain strong).

In a community circle, there are more communicators. The “atmosphere” — those who listen and give feedback — is the source of the communicators' continued expression. This means that the departure of any single member won’t impact the existence of the circle.

Once a community circle is established, its loyalty is extremely high. Even if the product ceases to exist, users will reunite elsewhere (e.g., “Neihan Duanzi” and “Jike” reincarnated on “Pipi Shrimp” and “Jellow”).

In a social circle, everyone is both an expressor and a listener. The emotional connection in such a circle transcends the product itself and can affect real-life relationships (e.g., early forum enthusiasts often held meetups and maintained long-term contact).

Underlying logic: “People” are the core value of a circle.

4. Summary

So, what type of circle should a product choose?

This depends on the structure of the user group’s “common traits.”

If most are beginners, a content circle can be formed by identifying an opinion leader.

If most are more advanced, a community circle can be developed.

If all users are highly experienced, a social circle might emerge.

On the other hand, a circle can only provide one type of informational value, but users at different stages have varying needs. Even advanced users still need basic needs met, so circles at different stages can coexist within a product.

For instance, in the product manager community, a content circle exists on the “Everyone is a Product Manager” website, a community circle exists on “Jike,” and a social circle exists in WeChat group chats. A product manager will use different products in different scenarios to meet personal needs, and even if they don’t, users will naturally create multi-stage circles.

In the case of forums, they are inherently community circles, but within them, the “essence” sections are closer to content circles, while chat sections lean towards social circles.

4. How to Build a Circle

Recently, more and more products are experimenting with the concept of a “circle.” In this section, we will discuss how a circle should be formed, what conditions and steps are necessary for its creation.

1. Required Conditions

A Suitable Theme

Different themes are suited for different types of circles. Some themes only account for a small portion of users' daily lives and can only form content circles (or even none at all). Other themes have the potential to form social circles.

A simple rule is: Short-term & low-frequency features are difficult to form a circle, while long-term & high-frequency features can.

For example:

"Nail Art" is difficult to form a circle because it’s a "low-frequency" feature — users might only get their nails done once a month, seek content when they want nail art, and then stop caring about it afterward.

"Motherhood" is easier to form a circle around because the need to take care of children is daily, and there are many different things to discuss every day.

A Sufficient Number of Users Who Can Form a Circle

As mentioned earlier, “people” are the core value of a circle, so finding the right people is one of the conditions for a circle’s formation.

For example, an "immediate product manager circle" can exist because there are many product managers using the platform. However, Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book) can’t form this circle, but it can form a "beauty circle" — something Ji Ke (another platform) might struggle to build.

Different types of circles require different user mixes and a sufficient user base.

For example, the conditions for a "content circle" include: having "a sufficient number of novice consumers willing to consume content" and "a few high-quality opinion leaders." If either side is lacking, the other will fail — like cooking: if the proportions and quantities are off, the dish will taste bad.

Channels to Aggregate People

If there are only potential users but no way to bring them together, users will remain loose individuals, not a circle.

Thus, a second condition for a circle is having “channels to aggregate people.”

In established products, there are often many such channels.

For example:

Baidu Tieba aggregates people through Baidu search, believing that "users searching for the same keyword" form the same circle.

WeChat subscription accounts aggregate users via the friend circle, thinking that "users who have added each other as friends" form the same circle.

On the other hand, Ji Ke struggles more because it lacks user profiles and search scenarios, so it can only push circles on the homepage, and this random aggregation is much less efficient.

2. Steps to Build a Circle

Earlier, we defined a circle as a "group with shared dependencies," not just a "group with relationships." The difference lies in whether “I am in the circle,” which depends on my attitude.

For example, simply "following" someone on Weibo doesn’t mean I’ve joined their “content circle”; it’s only when I depend on their content that I am part of their circle. This sense of dependency is built on long-term information input, and there are two steps involved in forming a circle.

Establish Information "Commitment"

An information "commitment" is a promise to continuously receive information.

For example:

Downloading an app means I’ve made a commitment to your content — I’ll view it when I actively choose to do so.

Following a Weibo account means I’ve committed to your content, and I’ll prioritize seeing it.

Joining a WeChat group means I’ve committed to your content, and I want to see it all the time.

The type of "commitment" depends on how much the user depends on the shared characteristics. The more advanced the circle, the more "higher-level commitments" it can ask of users.

However, there are various ways to prompt users to make a "commitment":

WeChat official accounts ask users to “follow” before they can view all content.

Weibo prompts users to "follow" after they’ve browsed for a while.

On the other hand, despite the different levels of commitment, all commitments must be stable. An unstable commitment will undermine the user’s sense of dependency. It’s like a breakfast shop — it needs to remain stable in one location to retain customers.

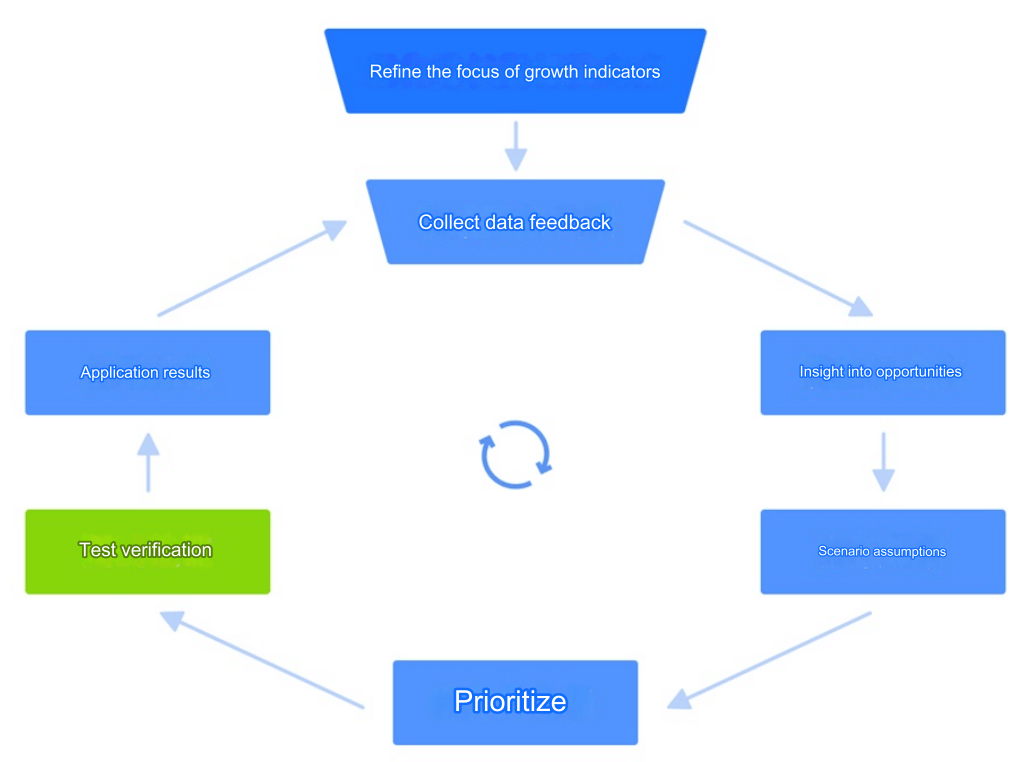

Information Transmission

People change their thoughts through “information,” and once the commitment is made, enough information needs to be transmitted to change the user’s mindset and establish a sense of dependency.

This doesn’t just include "content push" but also involves interface design, psychological cues, and other aspects when users enter the circle.

The type of information conveyed in different circles also depends on what users rely on.

For example:

In a content circle, users rely on "content," so you should convey information like "recent articles" or "best articles," to help users choose content.

In a community circle, users rely on "recognition," so you should convey member information, community rules, etc., to help users build a sense of belonging.

Over time, after a certain amount of "fermentation," a "circle" can be formed.

3. Summary

Building a circle requires persistent effort over time, allowing time to accumulate. Acting too hastily won’t work, and may lead to unexpected results.

On the other hand, while the process of building a circle seems simple, the necessary conditions are quite strict. Whether it’s “potential users” or “channels to aggregate people,” these are not things that a startup product can easily achieve.

"Circles" are more suitable for products with a certain scale and clear user profiles, using circles to cultivate user loyalty.

A good example is Meiyou. Meiyou is a tool product where users come and go, but it has the conditions to form a circle: first, there are a large number of young or expectant mothers, and second, users leave behind a lot of information on Meiyou that can be used to match circles. So, launching a circle on Meiyou was a natural move that also helped enhance user stickiness.

This is why most successful circles, like subscription accounts, Tieba, or Douban groups, were not independently created, but built upon larger platforms.

5. The Transitional State of Circles: "Temporary Circles"

Earlier, we defined a circle as a "group with shared dependencies."

“Dependency” is a long-term behavior, but due to limited human energy, there are only a few things people can rely on and only a few circles they can join.

Think about how many apps you’ve downloaded, how many official accounts you’ve followed, and how many you actually use regularly?

On the other hand, life is so diverse, and people face many problems, often requiring temporary things — like looking up tips while shopping or talking to someone when heartbroken. These needs aren’t long-term dependencies but short-term ones. This is the concept of "temporary circles."

1. Product Form of Temporary Circles

Temporary circles are not true circles; they’re designed to temporarily satisfy a user’s needs and have a stronger tool-like nature. A circle is a “group with shared dependencies,” while a temporary circle is simply “information with shared characteristics.”

In a content circle, a temporary circle would be “search” (including but not limited to), which briefly satisfies a user’s content needs.

In a community circle, a temporary circle would be a "topic," briefly satisfying the user’s communication needs.

In a social circle, a temporary circle would be a "chat room," briefly satisfying the user’s emotional needs.

These products are active on the internet, serving people who have varying degrees of reliance on shared characteristics.

2. Characteristics of Temporary Circles

Ability to Predict Circle Themes

Temporary circles briefly meet user needs, and if this “short-term satisfaction” becomes a “long-term habit,” it forms dependency — which is one of the elements needed to form a circle.

For example, high-frequency search content can indicate potential content circles, and high-frequency topics of discussion can predict potential community circles.

Ability to Transition Product Forms

In actual product evolution, temporary circles also play an important role in transitioning to a true circle.

At a large scale, search engines gave rise to media websites, and chat rooms gave rise to QQ groups. On a smaller scale, Ji Ke’s "circle" function evolved from its “topic” feature, and "chat rooms" were built upon “circles.”

Covers a Larger User Base

The number of people who are deeply reliant on shared traits is much smaller than those who temporarily need something, which allows temporary circles to cover a larger user base. Additionally, joining any circle creates psychological pressure (due to the commitment of receiving information), whereas using a temporary circle is much less burdensome, and it only needs to meet the need at that moment.

3. Summary

When considering temporary circles for your product, the basic logic remains the same as for circles — it depends on how much users rely on shared characteristics. Misestimating this will lead to incorrect usage.

For instance, many interest-based QQ groups are often set to "Do Not Disturb" as soon as users join. At this point, the group is no longer a social circle but a chat room — users only interact when they want to.

6. Circles in the Mobile Era

Earlier, we discussed the conditions required for a circle to form. In simple terms, products that can more accurately "aggregate the right user groups" will develop circles.

In the Web era, this aggregation was achieved via “search engines”—searching for the same keywords brought together a group of people, leading to the rise of blogs, Tieba, and forums. But with the decline of search engines, these platforms have also faded.

So, where are the circles in the mobile era?

Primary Entrance: Apps on Mobile Desktop

Mobile apps, as the fastest way to access content, have obvious dominance in the mobile era. Major circles are occupied by major apps.

For example:

Content circles like Toutiao, Douyin, and Douyu.

Community circles like Zhihu, Xiaohongshu, and Mafengwo.

They have large user bases, and therefore, they can afford substantial investments to support app development and operations, as well as extensive ad spending to aggregate the right audience and dominate user mindshare.

Secondary Entrance: Long Tail Circles in Small Blogs/Communities

Long-tail circles rely on more precise and segmented traffic, which in the mobile era comes from primary apps. Users are increasingly accustomed to searching for content on platforms like Xiaohongshu, WeChat, and Zhihu. This creates opportunities for niche circles like "anime figure circles" on Bilibili, "oily skin skincare circles" on Xiaohongshu, and "movie circles" on Douban.

Long-tail circles also have lower barriers to entry and require minimal investment to set up, making them an ideal space for smaller, specialized communities.

Currently, long-tail content circles are becoming more stable, and long-tail community circles are gradually being developed. Whether WeChat can replicate the success of subscription accounts in long-tail content circles or whether more major apps will emerge to compete for users will be one of the key changes in the coming years.

Summary

"Circle" products are essentially a common product structure, but with changing user habits, they are applied in different scenarios.

The general pattern is easy to follow:

Initially, users had mass content needs, leading to mass media products (e.g., 36Kr).

Later, users developed needs for mass community engagement, leading to large community platforms (e.g., Zhihu).

Then, users began to seek long-tail content, giving rise to long-tail media products (e.g., self-media).

Now, users have long-tail community needs...

This explains why "circles" have proliferated recently.

7. The Circle Product

When discussing "circles" in the context of products, it specifically refers to the "community circle" type, with "Ji Ke" (Jellow) and "WeChat Circles" as typical examples. There has been considerable discussion in the previous sections, and the following will delve deeper into this product form.

1. Why Did "Circle" Products Emerge Continuously Last Year?

As mentioned earlier, the basic condition for the creation of circles is that there is a group of users who share a dependency on common traits, which is a natural development in the history of content circles. The gradual maturity of this condition is the reason why circles emerged rapidly last year.

On the other hand, mainstream interest-based communities had already taken shape by last year. Platforms like Zhihu and Xiaohongshu had experienced significant growth in 2018, occupying major interest areas like "knowledge sharing" and "women's interests." However, the rapid influx of users led to an increasing gap between user groups. The homogeneous atmosphere of a single community could no longer support such a large user base, and conventional management strategies were insufficient to address all needs. Marginal users, whose interests didn’t fit the mainstream community culture, began to leave. The solution to bridging these gaps seems to be the "circle." This logic of sub-forums, an age-old concept in online communities, has become the new tool for content communities to engage users.

2. What Role Can a "Circle" Play?

Segmentation of Communities, Allowing Niche Cultural Users to Find Their Place

For example, a girl who loves hand-drawing shares her artwork on Xiaohongshu, but in a culture dominated by beauty and fashion, such posts may not receive much feedback. However, if there were a "hand-drawing circle," her artwork could be appreciated by like-minded people.

Facilitating Lighter, More Everyday Discussions, Leading to Higher Community Activity

Current interest-based communities are mostly content-heavy, designed to cater to the general public’s content consumption (suitable for attracting new users). However, this often results in communities being dominated by PGC (Professionally Generated Content), as seen on platforms like Bilibili and Xiaohongshu. Circles, by aggregating similar user groups, encourage lighter and more casual content creation and consumption. This complements "heavy content" by offering "light content" for discussion. For example, when I want to share a "boiled egg recipe," I might create a video or article for detailed expression. But if I just want to vent about buying fake eggs, I could simply complain in a "breakfast circle."

Providing Tools for Refined Operations

User diversity naturally requires refined operations, and circles are one of the tools for this refinement. They help aggregate similar users and provide a stable place to reach them.

For instance, before circles existed, organizing a "21-day breakfast challenge" could only be done through event pushes to segmented user groups, which were imprecise and had low engagement rates.

But with circles, an activity in the "breakfast circle" aligns with users' habits and participation is much higher due to a better community fit.

3. What Are the Characteristics of "Circle" Products?

A "circle" is essentially a "community," and its product characteristics are those of community products.

Sense of Group Identity

The key to distinguishing a "group of people" from a "circle" lies in the ability to form a "sense of group identity." This sense is reflected in various aspects of the community, such as common language features (slang): "Pipi shrimp—poke eyes," "Bilibili—AWSL" (a slang for admiration), and common behavioral norms: "Bilibili—spoiler warning," "Zhihu—conflict of interest statement."

In the design of circle products, this sense of group identity should be emphasized. Some common methods include:

Circle Entry Requests: Ensuring that all members share similar traits through reasons for joining.

Guidelines: Clarifying what can and cannot be done within the circle, controlling the content.

Theme Colors/Backgrounds: Customizing themes to suggest "This is a special place."

Member List: Displaying the composition and social structure of the members to indicate "We are a group."

Member Names: Using specific terms like "Goose group—Goose" to suggest "We are different from others."

Strong Interaction

While product design cues are important, the real key to forming a "group identity" is the interaction mechanism—high-frequency communication is essential for building group identity.

Currently, traditional posts and feeds are still the best option.

On one hand, they strike a balance between being lightweight enough to post casually without much effort, but not so fragmented as real-time chat. On the other hand, posts can accommodate various types of content, including links, addresses, polls, and giveaways, fulfilling various communication needs.

Some circle products also have "chat groups" for interaction, but I believe "chat rooms" are more appropriate. As mentioned earlier, we should choose content forms based on the level of user dependency on shared traits, and a "chat room" fits better for users who "occasionally depend on the group." It’s like most WeChat groups today: messages are muted by default, but users occasionally check in and chat.

Moreover, a circle must be large enough to sustain a chat room. Therefore, "posts" are the most suitable form of interaction for most circles, and if a circle has enough members, a "chat room" can enhance interaction frequency.

It’s worth mentioning Slack. This product, positioned between posts and instant chat, allows users to divide content into post sections and chat sections. This implicit division reflects real user needs.

Customization

Due to the varying needs of users in different circles, different functionalities are required. Similar to forums in the web era that used Disqus, but with different themes requiring different features.

Common customizations include:

Location/Product Circles: For example, a "Shanghai Food Circle" may require location-based content.

Trading Circles: For example, a "Figurine Trading Circle" would need features for showing product prices and marking items as available/sold.

Task Circles: Such as a "Breakfast Check-in" circle, where users can complete check-in tasks.

KOL Circles: Similar to "Knowledge Planet," where only KOLs and admins can post content.

8. Thoughts on Various Products

WeChat Circles

WeChat has all the conditions to develop long-tail circles. In its early stages, users sought content, so WeChat used subscription accounts to successfully develop long-tail content circles. Now, with users seeking interaction, WeChat has developed WeChat Circles to cater to long-tail community circles.

However, I think the issue with WeChat Circles lies in its product operation strategy. A feed centered around photo-sharing and submissions, without free communication, cannot form a community circle. Only fragmented and free discussions will work. Once the circle-building path is refined, with accurate user profiles and top-tier entrances, I am optimistic about the long-term development of WeChat Circles.

Feiliao

With the massive user base of ByteDance and its precise matching algorithms, Feiliao also has the potential to develop long-tail communities.

However, how to aggregate Toutiao and Douyin users into Feiliao is not only an operational strategy issue but also one of internal coordination.

Ji Ke / Jellow

A community built upon high-quality early users.

However, the challenges are: 1) The lack of a pre-existing user base, making the cost of acquiring new users via advertising too high; 2) The absence of accurate matching methods, leading to a large mismatch in user-circle funnels.

Thus, Ji Ke can only focus on optimizing retention with its existing user base. Expanding to a larger user base will require new tools or media-based scenarios.

Other purely circle-based products, such as "Lingyu" and "Island," face similar challenges. While they can be niche and beautiful, expanding further is quite difficult.

Dianping

With Dianping as a major community, expanding into niche communities is a natural next step and faces less interference from other products. However, a fundamental issue is that "eating out" is a low-frequency activity, and to create a more sticky circle, a higher-frequency main scene is needed.

Additionally, its operational strategy heavily favors KOL-driven content, and using "articles" for interaction incurs a higher cost, which is not conducive to forming a circle. But these issues are fixable.

Other Mainstream Communities

Platforms like Xiaohongshu, Zhihu, and Bilibili, like Dianping, are well-positioned to develop long-tail circles, provided their product and operational strategies are well-executed.

Knowledge Planet

Knowledge Planet developed its community circles based on KOL-driven content, solving the "preconditions" and "aggregation of people" issues. It is indeed a cold-start method for pure circle-based products. However, if mainstream interest-based community products create their own KOL circles, Knowledge Planet might lose its relevance. For instance, a food KOL with a broader potential audience on Dianping may not need to use Knowledge Planet.

Similarly, other KOL-focused circle products face the risk of being absorbed by mainstream interest-based communities, and I am not optimistic about the future of these circle products.

Conclusion

"Circle" products (community circles) are easy to understand, and the design of such products is similar across platforms. The main innovation lies in the "customization for different interest groups."

Overall, "circle" products (community circles) are a product form that is "difficult to attract new users but can boost activity and retention." Therefore, they are not suitable as standalone cold-start products but should be supplementary features to "mainstream communities," solving the problems of activity and retention. If giant long-tail circles emerge in the future, there is potential for them to become independent products.