One of my main methods of learning (and a hobby of mine) is reading financial reports. Each quarter, publicly traded companies release earnings reports, including announcements, press releases, and analyst call transcripts, which provide a wealth of financial and business information. This is a treasure trove of knowledge that should not be overlooked.

The quarterly financial disclosures of public companies, including announcements, press releases, and analyst call summaries, provide us with a wealth of financial and business information—a treasure trove of knowledge. In the past two years, since I found it hard to follow Hong Kong stocks and Chinese concept stocks, I've spent most of my time reading financial reports of U.S. tech stocks, including major companies like Microsoft, Apple, and NVIDIA, as well as influential companies like IBM in certain niches.

When I was in high school (around the time of the first dot-com bubble burst), IBM was one of the tech giants alongside Microsoft. Although its market value had fallen below Microsoft's, it still held significant weight. Over the next twenty years, IBM underwent multiple business restructurings, establishing a business model centered on enterprise software, while gradually exiting the ranks of "tech giants," with the gap between it and first-tier tech companies like Microsoft widening.

As of September 11, 2024:

IBM's market value is only 1/16 of Microsoft's, or more precisely, 6.14%. Last quarter, IBM's revenue was only 1/4 of Microsoft's, and its net profit was only 1/12 of Microsoft's; even its non-GAAP net profit was only 1/10 of Microsoft's.

In a context where IBM's scale is far smaller than Microsoft's, last quarter IBM's year-over-year revenue growth rate was only 2%, compared to Microsoft's 15%; IBM's net profit growth rate was slightly faster than Microsoft's (14% vs. 10%).

It's important to note that the above comparison is not entirely fair, as IBM had just completed the spin-off of its IT infrastructure and operations business in 2021, which became an independent publicly traded company named Kyndryl. However, even including Kyndryl, IBM's revenue only reaches about 30% of Microsoft's. Moreover, Kyndryl was spun off due to its slim profits, making it less appealing to the capital markets; its current market value is only about $5 billion (equivalent to 1/600 of Microsoft's).

In this generative AI-driven era, Microsoft's strategic position is far better than IBM's: the former is the largest external investor in OpenAI, and its Azure cloud platform is the most commonly used cloud for AI training. It has also fully integrated GPT into products and services like Office, Teams, and Bing; in contrast, IBM has become a less significant player, with its past glory represented by IBM Watson having faded. Now, IBM can barely rank in the second tier of AI technology. In the foreseeable future, the likelihood that the gap between Microsoft and IBM continues to widen is clearly much greater than the possibility of it narrowing.

So the question arises: How did IBM fall to this point?

It's worth noting that twelve years ago, on September 11, 2012, the gap between Microsoft and IBM was nearly negligible:

On that day, IBM's market value was $233.4 billion, while Microsoft's was $256.8 billion—both companies were essentially of the same scale.

In that quarter (July-September 2012), IBM's revenue was $24.7 billion, while Microsoft's was $16 billion; IBM's net profit was $3.8 billion, and Microsoft's was $4.5 billion. Both companies were still of similar scale.

Over the following twelve years, Microsoft's market value grew nearly twelvefold, while IBM's market value (considering the spin-off) stagnated. The widening gap in their market values mirrors the gap in their net profits, indicating that this change was driven by fundamentals, not just market whim.

Interestingly, during these twelve years, the management teams of both companies remained relatively stable: from 2012 to 2020, IBM was led by Ginni Rometty, who was succeeded by Arvind Krishna in 2021; while from 2014 to present, Satya Nadella has been the CEO of Microsoft. Thus, this question can largely be simplified to: What mistakes did IBM make during Rometty's tenure compared to Microsoft's successes under Nadella? Or, what correct actions did IBM fail to take?

There are certainly many reasons. I have neither served as a CEO of a multinational corporation nor worked in technology, so I can only offer my perspective as an observer. From a retrospective viewpoint, IBM has made mistakes in at least three major directions, in decreasing order of importance:

Failing to timely invest in cloud computing, especially public cloud services, thereby not adapting to the trend of "cloudification" in IT services.

Missing the wave of AI technology's shift to deep learning, which rendered its decades of AI technology accumulation quickly outdated.

Not betting on any consumer-facing (B2C) business, resulting in the loss of more possibilities (although betting might not have guaranteed success).

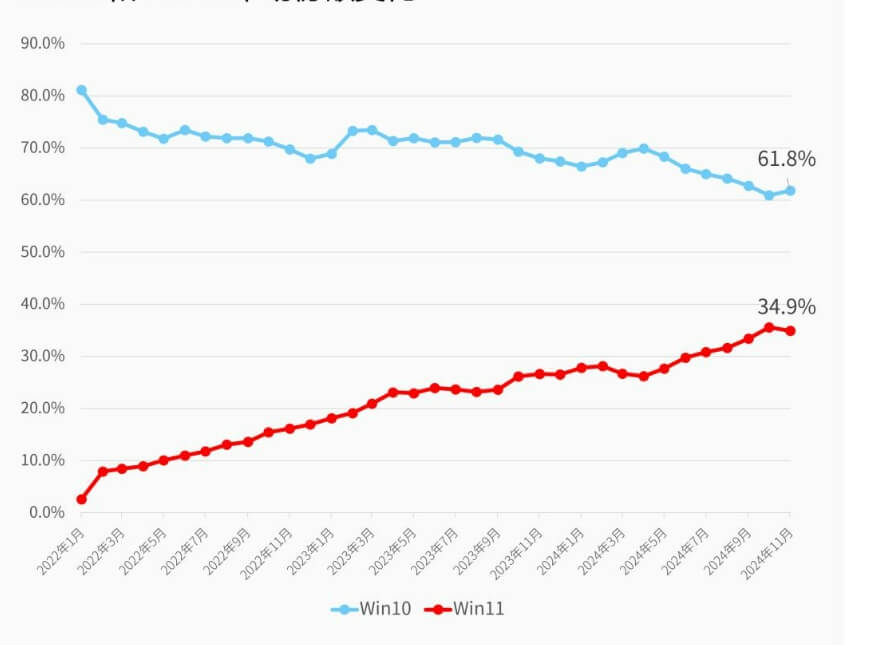

First, regarding the first point: Over the past twenty years, the most significant trend in global IT services has been cloud computing. Companies have gradually shifted from building their own IT systems to outsourcing to public cloud platforms, achieving comprehensive "cloudification" (or outsourcing) of IT infrastructure and software services. The pioneers in this space were Amazon, with AWS becoming its most profitable business (far more profitable than its core e-commerce business); next came Microsoft. Before becoming Microsoft’s CEO, Nadella was a key figure in the company’s transition to cloud computing, facilitating the integration of Microsoft’s databases, Windows servers, and development tools with Azure. Once he took over as CEO, Nadella decisively increased investment in Azure, turning it into Microsoft's revenue growth engine and its largest single revenue segment.

In fact, from a technical and product perspective, cloud computing is not directly correlated with Microsoft’s traditional business. Microsoft’s advantages in traditional PC and server software did not easily translate into advantages in cloud service; transitioning to the cloud was a long and painful process. The so-called "synergy between Microsoft's traditional business and cloud computing" mainly refers to sales synergy—Microsoft’s sales system (including direct sales personnel and distributors) covers a large number of enterprises, allowing these companies to be introduced to Azure cloud services. Microsoft’s existing customers can also receive certain discounts when purchasing Azure. This sales-based "advantage" is something IBM also possesses, as does Oracle, though the coverage varies.

In short, Microsoft's technological accumulation from the old era does not guarantee that Azure can catch up to Amazon's AWS in the new era. AWS was established as early as 2002 and began providing services in 2006; Azure was only founded in 2008 and began offering services in 2010. In the rapidly evolving field of cloud computing, a gap of 4-6 years is significant, requiring tremendous effort to catch up. When Nadella took charge of Microsoft’s cloud business, it was effectively the last window of opportunity for a comprehensive transition to cloud computing; had he waited another two years, Azure might have lagged behind the emerging Google Cloud! Nadella's "all-in Azure" decision was strategically monumental!

IBM's delay in cloud computing can be attributed to starting too late. In 2010, IBM began exploring cloud computing; it wasn't until 2013 that it established a real cloud services department through the acquisition of SoftLayer. Yet it was not until 2017 that IBM established a cloud services strategy centered on "hybrid cloud" (which can be seen as a combination of public and private clouds) and strengthened this strategy by acquiring Red Hat in 2018. By that time, the competitive landscape had already formed with Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google GCP as the dominant players, leaving IBM with a very limited market space primarily focused on large enterprise customers favoring hybrid cloud.

Ironically, according to IBM's official narrative, Rometty’s greatest achievement during her tenure as CEO was "establishing IBM’s hybrid cloud strategy." While this statement is accurate, this strategy should have been established in 2012-2013, not delayed until 2017-2018! “Delayed justice is no justice,” and similarly, a late correct decision can only become a mediocre decision. Moreover, hybrid cloud is not unique technology to IBM; Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and even Oracle can all offer it; even in this narrow niche market, IBM's position remains precarious.

Continuing to the second point, IBM once maintained a leading position in AI technology for fifty years. Friends from the '70s and '80s surely remember the 1996 match when Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov; Americans might also recall IBM Watson defeating human contestants in the quiz show Jeopardy! in 2011. A significant strategy during Rometty's tenure was to monetize IBM's AI technology through Watson solutions, initially targeting the healthcare industry.

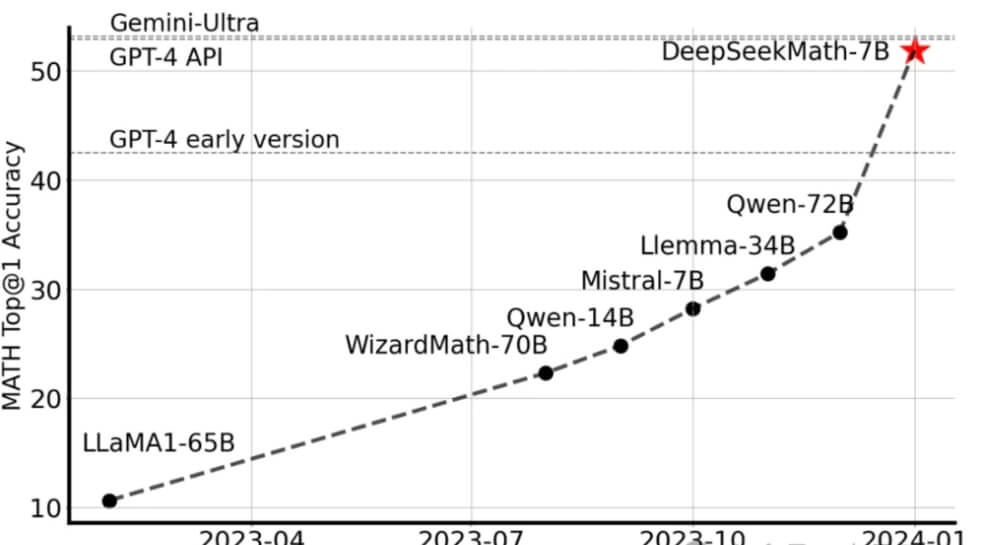

However, it turned out that the complexity of the U.S. healthcare system, with its numerous regulatory and ethical issues, was not conducive to AI transformation at that time, resulting in poor commercial performance for Watson. More importantly, a revolution in AI technology occurred around 2012-2013 (when Watson was beginning widespread commercialization): deep learning, based on neural networks, not only replaced traditional knowledge graphs (symbolism) but also supplanted traditional machine learning techniques like statistical learning, becoming the most efficient and widely applicable foundational technology for AI. In just a decade, deep learning revolutionized internet content distribution and advertising systems, spurring emerging industries such as autonomous driving and large language models (LLMs), becoming the absolute mainstream in academia.

As a long-standing AI technology leader, IBM failed to keep pace with the times; whether this was due to management decisions, insufficient resource investment, or low execution efficiency is no longer important. What matters is that while Google was acquiring AI startups based on deep learning at a rate of ten per year and luring top AI scientists like Ilya Sutskever and Andrew Ng with lucrative pay, IBM could only watch helplessly as its previous advantages dissolved.

While other tech giants were profiting from the wave of deep learning, IBM retained its old-school logic and technology. The heavy investment in Watson and the healthcare sector was effectively wasted as their technological architecture became outdated. The first example of this in recent years has been Google’s ChatGPT, which made IBM Watson completely lose its footing in AI; this gap is now insurmountable.

Finally, the third point is that IBM has not made any significant bets on B2C businesses in recent years. One significant transformation of tech giants in recent years has been the push into direct-to-consumer (D2C) channels. Although companies like Google and Amazon have been D2C from the start, many tech giants also made significant adjustments, such as Apple's strategic shift toward software services (including apps and subscriptions), and Microsoft's transition from purely B2B to incorporating B2C products (like Office 365 and Xbox). This trend has been especially evident in social media: Facebook's Messenger has morphed into a business platform, and TikTok has become a major advertising platform through influencer marketing.

While it is understandable that IBM, as an enterprise-centric company, focuses more on B2B, the past two decades have clearly demonstrated that the consumer market can also create substantial revenues and profits. When discussing the future of the IT industry, Rometty repeatedly stated that "technology is leading us into a new era," yet she missed significant opportunities to directly engage with consumers. This gap has cost IBM dearly; during her tenure, IBM made limited efforts in D2C projects.

In summary, when examining the decisions made during Ginni Rometty's tenure at IBM, there are at least three significant mistakes:

Delaying the cloud strategy, leading to loss of competitiveness in the cloud market.

Missing the deep learning revolution, allowing previous AI advantages to dissipate.

Not betting on D2C opportunities, thereby losing contact with the consumer market.

Ultimately, this analysis leads to a critical understanding: the past decade has been marked by extraordinary changes in technology and business landscapes. How a company adapts to these changes, makes bold decisions, and captures opportunities often distinguishes the winners from the losers. In the case of IBM, a combination of unfortunate decisions, missed opportunities, and a failure to adapt to changing market dynamics has placed it far behind Microsoft.

As a long-established AI technology leader, IBM has failed to keep pace with the times. Whether the reasons are mismanagement decisions, insufficient resource allocation, or low execution efficiency is now irrelevant. What matters is that while Google was acquiring AI startups based on deep learning at a rate of ten per year and luring top AI scientists like Ilya Sutskever and Andrew Ng with exorbitant salaries, IBM's actions were almost negligible. As a result, within just 2-3 years, Google seized the position of AI technology leader and quickly applied AI to services like search engines and translation, thus setting the "technology-application-commercialization" flywheel in motion. Unfortunately, it wasn't until 2021 that IBM admitted Watson's failure, by which time its foundational AI R&D capabilities had already been outpaced by Google, as well as fallen behind Amazon and Meta.

Strictly speaking, Microsoft was also a latecomer in this game; deep learning technology was never its strong suit. However, Microsoft made a remarkably correct decision by investing in OpenAI in 2019 and integrating its services into the Azure cloud platform. After the emergence of ChatGPT, everyone had to acknowledge that this was Microsoft's most important and successful strategic investment in its history. The deep collaboration with GPT not only boosted the sales of software services like Microsoft Office and Teams but, more importantly, established Azure as the "top cloud platform for AI services"—from 2023 onward, AI demand has consistently increased Azure's revenue growth by at least five percentage points each quarter. Now it’s Amazon that feels the crisis and is scrambling to find various countermeasures!

Of course, Microsoft hasn't pinned all its hopes on external investments; its internal R&D for generative AI has been ongoing. For example, it co-developed the trillion-parameter Megatron model with NVIDIA, and it is still developing and iterating on large models today. Over the past five years, as Azure has gradually released immense profitability and cash flow, Microsoft has been able to allocate more substantial resources to foundational R&D like generative AI, enabling mature business segments to "support" emerging ones. In contrast, IBM and Oracle lack such abundant resources to squander. Success begets success, much like money generates money; the key lies in the proper allocation of resources.

Lastly, regarding the third point: since selling its PC business to Lenovo in 2005, IBM has had little to show in terms of consumer-facing business. For nearly two decades, IBM has shown no interest in consumer-facing markets, whether in consumer internet, hardware, or content services. Fairly speaking, this cannot be considered a true "mistake," as IBM indeed lacks the genetic predisposition for consumer-facing business. Even if it had ventured into consumer business over the past decade, it would be difficult to predict what results it might have achieved.

The issue is that during the same period, Microsoft also had little genetic predisposition for consumer-facing business, yet it has repeatedly regrouped and fought back, tenaciously holding on. Investments in gaming have spanned the tenures of Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer, and Satya Nadella; while investments in smart hardware may have seen Microsoft stumble in the smartphone market, it has achieved some success in tablets, maintaining a strategic presence. Investments in consumer internet, primarily through the Bing search engine and LinkedIn, have overall been successful, especially as their strategic value has risen after integration with generative AI. It's worth noting that both the launch of Bing and the acquisition of LinkedIn occurred during Nadella's tenure.

We can see that during Ballmer's tenure as CEO, Microsoft struggled with consumer-facing business, often changing direction without a clear strategy; acquisitions of promising businesses often ended in failure. However, since Nadella took over, Microsoft's consumer-facing business has matured, with performance at least deemed adequate. From a financial perspective, today, all of Microsoft's consumer-facing businesses have achieved breakeven, including historically cash-burning gaming, thanks to the shift in positioning of the Xbox hardware platform. From the capital market's perspective, these divisions no longer drag down the company; their positive contributions to Microsoft's market value are increasingly evident.

Nadella's attitude toward consumer-facing business is epitomized in his explanation of the decision to acquire Activision Blizzard in early 2022: for a massive consumer business with over 3 billion users like gaming, Microsoft cannot afford to be absent. Similarly, one can infer that in Nadella's view, for Microsoft to maintain its status as a tech giant, it cannot retreat into the "comfort zone" of enterprise-level business; it must reach out. This is not only to establish direct connections with consumers and cultivate user mindsets but also to create business synergies—such as the synergy between AI and Bing, as well as the synergy between Azure and cloud gaming. In contrast, none of IBM's CEOs over the past two decades made a similar judgment; they all believed, without exception, that IBM could maintain its status as a tech giant solely by focusing on enterprise-level business or even just profitable large enterprise business. History has proven them wrong.

However, since IBM has already committed far more unforgivable errors in the strategic directions of cloud computing and AI, its lack of investment in consumer-facing business becomes less significant, even negligible. Ironically, IBM's most glorious moments in history coincided with its strongest consumer presence—during the 1980s to early 1990s, the IBM PC led the first wave of the information technology revolution into homes, until vibrant new competitors like Compaq, HP, and Dell overtook it. In the consumer PC market, Apple was once IBM's subordinate, but within just a few years, it resurrected itself and became a tech giant entirely rooted in the consumer market. The world is ever-changing, yet human agency plays a crucial role; whether it be "genetics" or "historical accumulation," it ultimately depends on execution.

02 Thus, we can better understand why CEOs in American publicly traded companies often receive extremely generous compensation:

According to Bloomberg, the average CEO compensation in U.S. public companies in 2022 was 400 times the average employee salary! Star CEOs like Elon Musk can pull in compensation packages worth billions of dollars annually. Nadella's compensation package in 2023 was $48.5 million; in 2013, before he became CEO, his compensation as Microsoft's Senior Vice President responsible for cloud computing was only $7.6 million.

Even considering inflation over the past decade, the disparity is still enormous!

Is this reasonable? Given the crucial role of CEOs, it clearly is. During Nadella's ten-year tenure as CEO, Microsoft's stock price increased tenfold; during Ballmer's tenure, it saw virtually zero growth. Had Rometty made at least one correct decision on cloud computing and AI strategic issues during her time as IBM CEO and executed it, IBM might still stand tall among tech giants today, with a market value potentially in the trillions instead of $185 billion. The American corporate governance structure grants CEOs nearly unlimited decision-making power, so they should bear responsibility for all errors while also being rewarded for all achievements. The so-called "unity of power and obligation" reflects this principle.

From this, we can further infer that in Chinese companies adopting an American corporate governance structure—mainly among internet companies—CEOs wield even greater power and responsibility. They not only enjoy the institutional authority granted by American companies but also possess unique non-institutional power from Chinese social dynamics, allowing them to implement their will more efficiently and thoroughly. When they make correct or incorrect choices, the impact on the company is magnified. Therefore, one could say that the success or failure of major internet firms can at least be attributed to their top executives; while this statement might seem extreme, it holds some truth.