Using Modules in Python

In the previous chapters, we have primarily been using the Python interpreter for programming. However, when you exit and re-enter the interpreter, all the methods and variables you defined disappear.

To solve this, Python provides a way to save these definitions in a file, which can then be used by scripts or interactive interpreter instances. This file is known as a module.

A module is a file that contains all the functions and variables you've defined, and it has a .py extension. Modules can be imported into other programs to utilize the functions and features within them. This is also how you use Python's standard library.

Below is an example of using a module from the Python standard library.

Example (Python 3.0+)

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Filename: using_sys.py

import sys

print('The command line arguments are:')

for i in sys.argv:

print(i)

print('\n\nThe Python path is:', sys.path, '\n')The output of the above code when executed is as follows:

$ python using_sys.py argument1 argument2 The command line arguments are: using_sys.py argument1 argument2 The Python path is: ['/root', '/usr/lib/python3.4', '/usr/lib/python3.4/plat-x86_64-linux-gnu', '/usr/lib/python3.4/lib-dynload', '/usr/local/lib/python3.4/dist-packages', '/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages']

Key Points:

import sysimports thesys.pymodule from the Python standard library. This is how you import any module.sys.argvis a list that contains the command line arguments.sys.pathis a list of directories that the Python interpreter searches for required modules.

Import Statement

To use a Python source file, all you need to do is execute the import statement in another source file. The syntax is as follows:

import module1[, module2[,... moduleN]]

When the interpreter encounters an import statement, it imports the module if it is in the current search path.

The search path is a list of directories that the interpreter searches to find a module. To import the module support, you should place the command at the top of your script:

Example of support.py file:

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Filename: support.py

def print_func(par):

print("Hello:", par)

returnExample of importing support.py in test.py:

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Filename: test.py

# Import the module

import support

# Now you can call the functions contained within the module

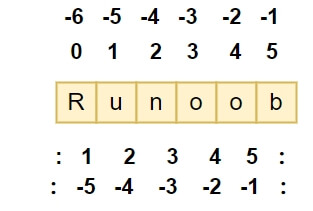

support.print_func("Runoob")Output of the above example:

$ python3 test.py Hello: Runoob

Importing Modules in Python

A module in Python is only imported once, no matter how many times you use the import statement. This prevents the module from being executed repeatedly upon multiple imports.

When we use the import statement, how does the Python interpreter locate the corresponding file?

This involves Python's search path, which consists of a list of directory names that the interpreter searches through to find the imported module. This is similar to environment variables, and in fact, you can define environment variables to specify the search path.

The search path is determined during the compilation or installation of Python, and installing new libraries can modify it. The search path is stored in the sys module’s path variable. Let's try a simple experiment in the interactive interpreter by inputting the following code:

>>> import sys >>> sys.path ['', '/usr/lib/python3.4', '/usr/lib/python3.4/plat-x86_64-linux-gnu', '/usr/lib/python3.4/lib-dynload', '/usr/local/lib/python3.4/dist-packages', '/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages']

The output of sys.path is a list, with the first entry being an empty string '', which represents the current directory (if printed from a script, it will be clearer which directory it is). This is the directory where we execute the Python interpreter (for scripts, it's the directory where the script resides).

Therefore, if you have a file with the same name as the module you want to import in the current directory, it will mask the actual module.

Modifying sys.path

Now that you understand the concept of the search path, you can modify sys.path in a script to import modules that aren't in the search path.

Let’s create a file fibo.py in the current directory or a directory in sys.path with the following content:

# Fibonacci series module def fib(n): # Prints Fibonacci series up to n a, b = 0, 1 while b < n: print(b, end=' ') a, b = b, a + b print() def fib2(n): # Returns Fibonacci series up to n result = [] a, b = 0, 1 while b < n: result.append(b) a, b = b, a + b return result

Importing the fibo Module

Now, enter the Python interpreter and import this module:

>>> import fibo

This does not write the functions defined in fibo into the current namespace, but it does add the module name fibo to it. You can access the functions by using the module name:

>>> fibo.fib(1000) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987 >>> fibo.fib2(100) [1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89] >>> fibo.__name__ 'fibo'

If you plan to use a function frequently, you can assign it to a local name:

>>> fib = fibo.fib >>> fib(500) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377

The from ... import Statement

Python’s from statement allows you to import specific functions or variables from a module into the current namespace. The syntax is:

from modname import name1[, name2[, ... nameN]]

For example, to import the fib function from the fibo module:

>>> from fibo import fib, fib2 >>> fib(500) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377

This statement does not import the entire fibo module into the current namespace, but only the specified functions.

The from ... import * Statement

You can import everything from a module into the current namespace using the following statement:

from modname import *

This is a convenient way to import all items from a module. However, this method should be used sparingly.

Understanding Modules

A module can contain executable code along with function definitions. This code is typically used to initialize the module and is executed only once, when the module is first imported.

Each module has its own private symbol table, which serves as the global symbol table for all functions defined within the module. This allows the module author to use global variables inside the module without worrying about accidentally interfering with other users' global variables.

You can access functions and variables within the module using modname.itemname. Modules can also import other modules. At the beginning of a module or script, use import to bring in the necessary modules—this is a common convention but not mandatory.

Importing Specific Names

You can also import specific names from a module directly into the current module’s namespace:

>>> from fibo import fib, fib2 >>> fib(500) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377

This does not place the module name (fibo) in the current namespace, so in this example, the name fibo is undefined.

Importing All Names from a Module

To import all the functions and variables from a module into the current namespace at once:

>>> from fibo import * >>> fib(500) 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377

This imports all names, except those that start with a single underscore (_). However, this method is rarely used by Python programmers, as it risks overwriting existing definitions.

The __name__ Attribute

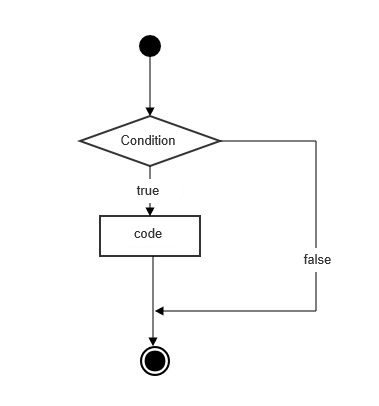

When a module is first imported into another program, its main program will run. If we want to prevent a certain block of code in the module from executing when the module is imported, we can use the __name__ attribute to ensure that this code only runs when the module is executed directly.

#!/usr/bin/python3

# Filename: using_name.py

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('The script is running directly')

else:

print('I was imported from another module')Running this script produces the following output:

$ python using_name.py The script is running directly $ python >>> import using_name I was imported from another module

Explanation: Every module has a __name__ attribute. When the value of __name__ is '__main__', it means the module is being run directly. Otherwise, it indicates the module is being imported.

Note: __name__ and __main__ are surrounded by double underscores, like _ _name_ _ and _ _main_ _ without spaces.

The dir() Function

The built-in dir() function can be used to find all the names defined in a module. It returns these names as a list of strings:

>>> import fibo, sys >>> dir(fibo) ['__name__', 'fib', 'fib2'] >>> dir(sys) ['__displayhook__', '__doc__', '__excepthook__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__stderr__', '__stdin__', '__stdout__', '_clear_type_cache', '_current_frames', '_debugmallocstats', '_getframe', '_home', '_mercurial', '_xoptions', 'abiflags', 'api_version', 'argv', 'base_exec_prefix', 'base_prefix', 'builtin_module_names', 'byteorder', 'call_tracing', 'callstats', 'copyright', 'displayhook', 'dont_write_bytecode', 'exc_info', 'excepthook', 'exec_prefix', 'executable', 'exit', 'flags', 'float_info', 'float_repr_style', 'getcheckinterval', 'getdefaultencoding', 'getdlopenflags', 'getfilesystemencoding', 'getobjects', 'getprofile', 'getrecursionlimit', 'getrefcount', 'getsizeof', 'getswitchinterval', 'gettotalrefcount', 'gettrace', 'hash_info', 'hexversion', 'implementation', 'int_info', 'intern', 'maxsize', 'maxunicode', 'meta_path', 'modules', 'path', 'path_hooks', 'path_importer_cache', 'platform', 'prefix', 'ps1', 'setcheckinterval', 'setdlopenflags', 'setprofile', 'setrecursionlimit', 'setswitchinterval', 'settrace', 'stderr', 'stdin', 'stdout', 'thread_info', 'version', 'version_info', 'warnoptions']

If no parameters are provided, dir() lists all names defined in the current module:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] >>> import fibo >>> fib = fibo.fib >>> dir() # List of attributes currently defined in the module ['__builtins__', '__name__', 'a', 'fib', 'fibo', 'sys'] >>> a = 5 # Create a new variable 'a' >>> dir() ['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', 'a', 'sys'] >>> >>> del a # Delete variable 'a' >>> >>> dir() ['__builtins__', '__doc__', '__name__', 'sys']

Standard Modules

Python comes with a set of standard modules, which are covered in the Python Library Reference (referred to as the "library reference").

Some modules are built directly into the interpreter. While these are not language features per se, they are highly efficient and can even handle system-level calls.

These components are configured differently depending on the operating system. For example, the winreg module is only available on Windows systems.

Note that there is a special module called sys, which is built into every Python interpreter. The variables sys.ps1 and sys.ps2 define the strings for the primary and secondary prompts:

>>> import sys

>>> sys.ps1

'>>> '

>>> sys.ps2

'... '

>>> sys.ps1 = 'C> '

C> print('Runoob!')

Runoob!

C>Packages

A package is a way of organizing Python module namespaces by using "dotted module names."

For example, a module named A.B represents a submodule B within the package A.

Just as you don't have to worry about global variables interfering between different modules, using dotted module names prevents conflicts between modules with the same name across different libraries.

For instance, different authors can provide their own NumPy module or Python graphics libraries.

Suppose you want to design a unified set of modules (or a "package") for handling audio files and data.

Since there are many different audio file formats (distinguished mainly by their extensions, such as .wav, .aiff, .au), you'll need a growing set of modules to handle conversions between these formats.

Additionally, there are many different operations for audio data (e.g., mixing, adding echo, EQ functionality, creating synthetic stereo effects), so you'll need a variety of modules to manage these tasks.

Here is an example of a possible package structure (in a hierarchical file system):

sound/ # Top-level package __init__.py # Initialize the sound package formats/ # Subpackage for file format conversions __init__.py wavread.py wavwrite.py aiffread.py aiffwrite.py auread.py auwrite.py ... effects/ # Subpackage for sound effects __init__.py echo.py surround.py reverse.py ... filters/ # Subpackage for filters __init__.py equalizer.py vocoder.py karaoke.py ...

When importing a package, Python searches the directories in sys.path for the package's subdirectories.

A directory is recognized as a package only if it contains a file named __init__.py, which helps avoid conflicts with other modules in the search path.

The simplest case is to place an empty __init__.py file. This file can also contain initialization code or set the __all__ variable, which we'll discuss later.

You can import specific modules from a package, for example:

import sound.effects.echo

This imports the submodule sound.effects.echo. It must be accessed using the full name:

sound.effects.echo.echofilter(input, output, delay=0.7, atten=4)

Alternatively, you can import the submodule directly:

from sound.effects import echo

This imports the submodule echo and allows you to use it without the lengthy prefix:

echo.echofilter(input, output, delay=0.7, atten=4)

You can also import specific functions or variables:

from sound.effects.echo import echofilter

This imports the function echofilter from the echo submodule, allowing you to use it directly:

echofilter(input, output, delay=0.7, atten=4)

Note: When using from package import item, the item can be a submodule, subpackage, or any other name defined within the package, such as functions, classes, or variables.

The import syntax first attempts to find item as a package. If not found, it tries to import it as a module. If it still fails, an ImportError is raised.

Conversely, using import item.subitem.subsubitem requires that all items except the last be packages. The last item can be a module or package but not a class, function, or variable name.

Importing All Names from a Package

What happens if we use from sound.effects import *?

Python will search the file system, find all submodules within the package, and import them one by one.

However, this method doesn't work very well on Windows due to its case-insensitive file system. On Windows, it's unclear whether a file named ECHO.py should be imported as echo, Echo, or ECHO.

To address this, a precise package index must be provided.

Import statements follow this rule: if the package’s __init__.py file contains a list variable named __all__, then from package import * will only import the names listed in __all__.

As a package author, remember to update __all__ whenever you update the package.

Here’s an example from sound/effects/__init__.py:

__all__ = ["echo", "surround", "reverse"]

This means that using from sound.effects import * will only import these three submodules.

If __all__ is not defined, using from sound.effects import * will not import any submodules of the sound.effects package. It will just import the package and its defined contents, possibly running initialization code in __init__.py.

For instance:

import sound.effects.echo import sound.effects.surround from sound.effects import *

Importing Modules from Packages

In this example, before executing from...import, the echo and surround modules from the sound.effects package have already been imported into the current namespace. (Of course, if __all__ is defined, this issue is avoided.)

Typically, using the * method for importing modules is not recommended because it often reduces code readability. However, it can save a lot of typing and some modules are designed to be imported in this specific way.

Remember, using from Package import specific_submodule is always a safe method. In fact, it is the recommended approach unless there is a risk of the submodule name conflicting with other packages.

If a package is a subpackage (e.g., the sound package in this example), and you want to import a sibling package (a package at the same level), you should use absolute import paths. For example, if the sound.filters.vocoder module needs to use the echo module from the sound.effects package, you would write:

from . import echo from .. import formats from ..filters import equalizer

Relative imports, whether implicit or explicit, start from the current module. The name of the main module is always "__main__", so a Python application’s main module should always use absolute paths for imports.

Packages also provide an additional attribute, __path__. This is a list of directories, each containing an __init__.py file that serves the package. You must define this before any other __init__.py files are executed. You can modify this variable to affect the modules and subpackages contained in the package.

This feature is not commonly used and is generally reserved for extending the modules within a package.