No Overtime, and They Still Built the World's Largest Company. The Employees Are So "Lazy," Yet Microsoft Is So Rich and Innovative. This Doesn’t Make Sense!

01

In 2008, Zhang Yiming worked as a manager at Kuxun, overseeing a team of 40 employees, but he felt he had hit a management bottleneck. So, he crossed mountains and seas to become an employee at Microsoft.

Zhang Yiming initially joined Microsoft to learn about managing a large company, but he left after only six months. When reflecting on his time at Microsoft, he described it in two words: boring.

“Half the day was work, and half the day was reading. The work was not very challenging,” Zhang Yiming said.

The boredom of working at Microsoft was not felt only by Zhang Yiming, who was determined to make a big impact. One of his friends once shared, “The team I joined at Microsoft was too relaxed. The team leader was rarely seen, and when they did show up, they would just talk about skiing and other leisure activities.”

Later, this friend transferred to another team, citing the lack of challenge as detrimental to his personal career development. The other team, which was busier, had a daily schedule of 10 AM to 5 PM, with a seven-hour workday, and employees were paid the highest hourly rate in the area.

In the IT circle, Microsoft, Intel, and EMC are known as the “three retirement homes,” where the work is easy, and employees are “lazy.”

In 2020, Microsoft Japan announced a four-day workweek, giving employees three days off, starting the “three-day weekend system.” This week, LinkedIn, owned by Microsoft, also announced that all employees would get a paid week off—not for statutory holidays or labor law compliance, but simply to improve employee happiness.

Microsoft also allows some employees to work remotely on a regular basis, up to 50% of their working hours. With manager approval, some can even work remotely full-time. For employees working permanently from home, Microsoft covers their office-related expenses. If they feel like returning to the office after working from home for a while, Microsoft has flexible office spaces available for them to use.

▲ Microsoft’s hardware lab in Redmond, Washington, where employees can work from home

Yet, despite being so “lazy,” Microsoft has achieved incredible results.

Microsoft's current market value is $1.93 trillion, which is equivalent to three times the market cap of Alibaba ($661.8 billion) or five times ByteDance ($400 billion). A further 5% increase, and this tech giant may join Apple in the $2 trillion market cap club.

In fact, on February 11, 2020, Microsoft briefly surpassed Apple to become the world's most valuable tech company.

Microsoft holds the highest market share in traditional operating systems and office software, both at over 97%. Its innovative businesses, including cloud computing, AR, and gaming, continue to perform strongly.

In cloud computing, 95% of Fortune 500 companies use Microsoft’s Azure cloud services.

In AR, Microsoft received a $22 billion order earlier this month. According to an IDC report, global AR-related spending is forecast to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 54% between 2020 and 2024, exceeding $70 billion.

In gaming, Microsoft is one of the three major console gaming brands, with its Xbox console holding nearly a third of the market share at 26%. It also dominates the PC gaming sector.

In March 2020, Microsoft acquired Zenimax Media, the parent company of the well-known game giant Bethesda Softworks. Bethesda owns globally recognized franchises such as The Elder Scrolls, Fallout, and Dishonored, with significant influence in the gaming industry. The acquisition caused a stir in the industry and even prompted joint scrutiny from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the European Union.

▲ Microsoft’s exclusive games

This raises the question: If Microsoft is so “lazy,” how is it still so successful and competitive? How does it lead innovation?

02

Microsoft has not always been a "good boy" when it comes to company governance. It wasn't always a friendly employer.

In its early entrepreneurial stages, Microsoft was not employee-friendly. Employees not only had to work long hours but also faced the possibility of being publicly humiliated at any moment. During its mid-growth stage, Microsoft faced multiple antitrust investigations, struggles in its foray into the internet, and performance pressures, which led to even stricter demands on its employees. Later, during the company’s business transformation phase, Microsoft gained attention for things like launching negative ads against competitors and even making headlines for throwing phones at its own employees.

In an interview on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs program, Bill Gates admitted that in the early days of Microsoft, he was “fanatical about work,” and this was unfortunate for his colleagues.

When Microsoft was founded in 1975, the company was still in its infancy, with only a few employees. To increase efficiency, Bill Gates would work around the clock, living and eating at the office, and sometimes going weeks without changing his clothes. He imposed his almost obsessive work habits on his employees. At one point, Gates even used car license plates to track employees' working hours, preventing tardiness or early departures.

“I knew everyone’s license plate, so I could just look at the parking lot to know when they arrived or left work,” Bill Gates said.

▲ A scene from the documentary Inside Bill’s Brain: Decoding Bill Gates, showing that despite being incredibly busy, Bill Gates still made time for two major hobbies: road racing and watching striptease shows.

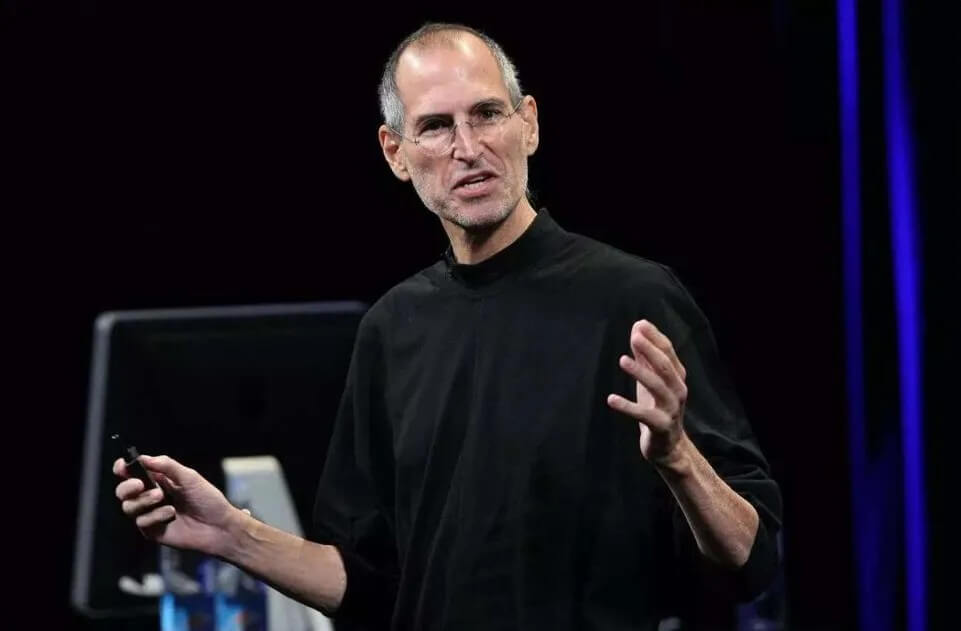

Bill Gates worked like a maniac, but in his view, one of his clients was even more ruthless—someone who couldn't even be called a workaholic. That person was Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple.

At that time, the Apple II needed a suite of office software. Bill Gates worked day and night to create the early versions of Word, Excel, and other office software, but often faced relentless pressure from Jobs to hurry up.

Gates described Jobs as “fanatical about work” and “demanding.”

When two workaholics clash, especially when both are founders of tech companies, their employees suffer.

In Silicon Valley Legends, it is mentioned that Steve Jobs had a volatile temper in his early years and even took advantage of co-founder Steve Wozniak, giving him less stock than he deserved.

Image

Bill Gates would attend product review meetings and take pleasure in berating employees. Employees even used the number of times he said "fxxk" as a benchmark for whether their product designs would pass.

Microsoft engineer Borski once wrote on his blog about Gates' behavior:

“He didn’t really want to review your design; he just wanted to make sure you had mastered it. According to his usual standards, he would ask increasingly difficult questions until you admitted you didn’t know the answer, and then he would berate you for being unprepared. If you could answer the hardest question he asked, no one knew what would happen next, because no one had ever done that before.”

Bill Gates had a reputation for being harsh and would not only berate employees but also co-founder Steve Ballmer. Leaked emails between Gates and Ballmer were often “intense.”

This culture of yelling continued, especially after Ballmer took over as Microsoft’s CEO, and he became known for his outbursts.

In September 2009, in Seattle, during a time when Microsoft was struggling with the failure of Windows Vista, the decline of Windows Mobile due to competition from Google and Apple, and poor sales of the Zune music player compared to the iPod, Microsoft was also envious of Apple’s iPhone. Within a year, Microsoft released two generations of multimedia phones, Kin 1 and Kin 2, which collectively sold only 500 units.

On September 14, 2009, Ballmer smashed an employee's phone during an internal meeting at Microsoft.

At the time, Ballmer was his usual energetic self, but when he saw someone taking photos with an iPhone, he rushed over, grabbed it, mocked it, and threw it on the ground, stomping on it.

Ballmer had also thrown chairs at employees and, after a senior executive left for Google, he infamously yelled, “I’m going to bury Google’s CEO Eric Schmidt! I’m going to destroy Google!”

▲ Ballmer’s iconic "8 stars and 8 arrows" TV ad from 1986

This angry culture persisted in Microsoft employees' work habits, to the point where in the Windows 10 Dev Build 21313 version update, engineers wrote on the update page: “Configuring updates, please don’t TM turn off the computer.”

Today, as Bill Gates transforms into a more gentle, older figure, he has begun to reflect on his relationship with employees:

“I have to remind myself not to hold my own standards for working hard against my employees anymore.”

03

Previous Generations Plant Trees, and Future Generations Enjoy the Shade.

Microsoft’s 50-year history, from corporate governance disasters to now being the "retirement home" of the tech industry, reflects that it was not so much a deliberate decision by Microsoft to improve employee welfare, but rather a result of being forced into it.

According to historian Thomas McCraw's research, between 1897 and 1904, 4,227 U.S. companies merged into 257. By 1904, about 318 trusts controlled two-fifths of the nation's manufacturing assets. Following this, the U.S. went through three waves of antitrust actions, each of which promoted improvements in employee welfare and corporate governance while fostering technological advancements.

During the first antitrust wave in 1890, the U.S. enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act, breaking up trusts like Rockefeller's and the Morgan family's, which allowed new companies such as Ford and Chevrolet to grow. The "eight-hour workday" and similar reforms began to be implemented.

In the second antitrust wave in 1970, telecom giants like IBM and AT&T were penalized and nearly broken up. These companies loosened their monopolistic control over technology and addressed harmful competition and bundled sales practices. This opening up of technology allowed companies like Microsoft, Intel, and HP to grow, while issues like excessive overtime in the telecom industry improved. As Silicon Valley developed, systems like flat management and flexible working hours became more widespread.

In 1998, Microsoft, once a knight slaying dragons, became the "dragon" itself, using its operating system monopoly to venture into the browser market. It wasn't until Google launched Chrome in 2008 that Internet Explorer's ten-year dominance was finally ended. These ten years depleted the early internet advantages of the U.S., while companies from China, India, and South Korea began to flourish, and Facebook and Amazon rose to prominence.

Having lost its monopoly advantage, Microsoft realized that its previous method of exploiting employees to gain scale and maintain monopolistic profits no longer worked. Meanwhile, more lenient tech companies like Facebook were aggressively poaching its talent. Their approach was simple and direct: higher salaries, fewer working hours, and more flexible working arrangements.

Silicon Valley entered a positive cycle of employee welfare: talent was limited, but business expansion was unlimited. To attract top talent, companies began going all out to improve employee benefits.

For example, Google built dedicated bike lanes for employees; Facebook expanded maternity leave, offering male employees four months of leave; Apple offered female employees up to $20,000 for egg freezing.

Microsoft, with its financial resources, leveraged its "cash power" to compete with the employee benefits of Silicon Valley tech companies.

Ultimately, Microsoft’s improvement in employee welfare and corporate governance was the result of both internal and external factors.

On one hand, Microsoft’s traditional business was shackled by antitrust restrictions, and there was little room for further breakthroughs. Continuing to exploit employees became meaningless. At the same time, Microsoft’s new business growth areas in cloud computing, AR, and gaming required more efficient operations and creative development rather than the mass recruitment and overtime culture of the past.

On the other hand, in the past decade, traditional tech companies faced new competition from internet companies, and Microsoft needed to offer better employee benefits to attract talent. Developed markets like Europe, the U.S., and Japan also faced significant demographic challenges, such as low birth rates and a lack of available engineers, which objectively increased the bargaining power of employees. There was simply no talent to spare.

Additionally, due to stringent U.S. labor laws like the Labor Law and Employment Law, companies like Microsoft faced significant labor lawsuits and compensation costs. Numerous labor rights lawyers sought huge labor compensation through disputes, while unions in the U.S. were deeply ingrained, offering free legal assistance to workers in exchange for mediation fees from companies.

04

Whether Silicon Valley companies or domestic firms, they all inevitably fall victim to the “big company disease” today:

Meaningless yet endless meetings and PowerPoint summaries, seemingly strict management that actually reduces efficiency through layers of approval, and employees who appear to be working overtime but are, in reality, under pressure and disengaged.

This condition is incurable, causing companies to become bloated and unable to adapt to market changes. Silicon Valley invented various management tools like KPIs (Key Performance Indicators), OKRs (Objectives and Key Results), agile development, and garage plans, but their effects were minimal.

Microsoft and IBM are no different. When a company reaches a certain scale, it suffers from “big company disease”—departments work in silos, internal politics overshadow the voice of customers, and the response time becomes slow. The gap compared to emerging companies is clear.

IBM’s solution was layoffs and business divestments, controlling the company’s size and reducing layers of management to make operations more agile. Microsoft, however, chose to confront the issue head-on. Around 2011, current CEO Satya Nadella started reforms with the least resistance in the technology sector, ultimately reforming the company’s culture and governance.

The most successful aspect of Nadella’s Microsoft was breaking down department silos and cliques, but without outright dismissing the existing departmental structure.

According to Coase’s theory, when an organization becomes large enough, there is practically an "organizational boundary" between departments. This is a real sociological phenomenon that cannot be ignored.

Microsoft essentially accepted departmental boundaries and factionalism because they were unavoidable. Even Bill Gates admitted, “When the company grew to a certain size, I had to relax these standards.”

Microsoft’s strategy was “the company serves the growth of its employees”: If engineers need to be cool, create the conditions for them to be cool; if hiring by department is too complicated, hire people by specific function and let them be responsible for their own work, without needing to answer to department heads.

In fact, Microsoft did not radically dismantle the traditional hierarchical department system. Instead, it empowered lower-level employees, making it easier to achieve objectives and increasing overall efficiency within the company.

For startups, employees are like a stretched spring, and the company needs them to go all out to win the market. But for large companies, treating employees like a stretched spring can backfire—stretch too far, and the spring won’t snap back.

For example, after Microsoft Japan implemented the “four-day work, three-day off” system, Microsoft reported a 39.9% increase in labor productivity compared to the previous year. Between extending working hours and improving efficiency, Microsoft chose the latter.

From Microsoft’s experience, under Steve Ballmer, employees worked overtime a lot, but the company’s performance growth was limited. Under Nadella, employees were much happier, yet the company’s market value approached $2 trillion.

Microsoft summarized its corporate governance lessons in three points:

-

Improving employee welfare can boost productivity, not the other way around. This is particularly true in high-tech and creative industries, where efficiency is more important than overtime.

-

The “big company disease” cannot be eradicated, but it can be managed.

-

The level of corporate governance depends on senior management. Don’t expect middle and lower management to contribute to company culture. The final decision on whether employees work overtime lies with the founders and the executive team.

Since last year, with the continued support of OpenAI and its own increasing investments in cloud computing and artificial intelligence, Microsoft has not only returned to its historical peak but also set new records, doubling its stock price in one year and surpassing Apple with a market value exceeding $3 trillion, becoming the world’s largest company by market capitalization.

This proves the effectiveness of the above three principles and demonstrates that innovation and efficiency can come from avoiding overtime and resisting internal competition.

Of course, achieving this is not easy.